Quaderns de Psicologia | 2025, Vol. 27, Nro. 3, e2176 | ISSN: 0211-3481 |

https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.2176

https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.2176

Exposure to Family Violence and Child-to-Parent Violence: Dispositional Mindfulness as a Protective Factor

Exposición a la violencia familiar y violencia filio-parental: mindfulness disposicional como factor protector

Sara Rodriguez-Gonzalez

Nerea Cortazar

Joana Del Hoyo-Bilbao

University of Deusto

Abstract

Despite growing evidence between exposure to family violence and child-to-parent violence (CPV), there are hardly any studies that assess protective factors. Some of the dispositional mindfulness (DM) dimensions are protective against internalizing and externalizing symptoms. The aim of the study was to analyze the moderating role of five DM dimensions in the relation between exposure to family violence and physical and psychological CPV among parents. Participants completed CPV, DM, and exposure to family violence measures (n = 415, age range = 18-25). Observing was associated with lower CPV levels, whereas non-judging had an ambivalent role depending on the CPV form. In addition, three facets of mindfulness—specifically, describing, observing, and non-reactivity—showed a moderating role by buffering the effect of exposure to family violence on CPV.

Keywords: Child-to-parent violence; Dispositional mindfulness; Youth; Family

Resumen

A pesar de la creciente evidencia en exposición a violencia familiar y violencia filio-parental (VFP), apenas hay estudios que evalúen los factores de protección. Algunas de las dimensiones de mindfulness disposicional (MD) son protectoras frente a síntomas internalizantes y externalizantes. El objetivo del estudio fue analizar el papel moderador de las cinco dimensiones de DM en la relación entre la exposición a la violencia familiar y la VFP física y psicológica hacia las figuras parentales. Los/as participantes completaron medidas de VFP, MD y exposición a la violencia familiar (n = 415, rango de edad = 18-25). “Observar” se asoció con niveles bajos de VFP, mientras que “no juzgar” tuvo un papel ambivalente dependiendo de la forma de VFP. Además, tres de las facetas del MD —específicamente, describir, observar y no reaccionar— mostraron un papel moderador amortiguando el efecto de la exposición a la violencia familiar sobre la VFP.

Keywords: Violencia filio-parental; Mindfulness disposicional; Juventud; Familia

Introduction

Child-to-parent violence

Adolescence and youth are periods involving changes that affect on a socioemotional, physical, and psychological level (Branje, 2018; Calvete, Orue et al., 2020). These changes can generate conflicts within the family environment (Branje, 2018; Calvete et al., 2011). These conflicts escalate when family members resort to aggressive behaviors as a problem-solving method (O’Hara et al., 2017), which can lead to more severe problems such as child-to-parent violence (CPV) (Calvete et al., 2017). CPV are recurrent psychological, physical, and economic violent behaviors by children against parental figures (Pereira et al., 2017). This kind of intrafamilial violence is exercised to a greater extent toward mothers (Calvete et al., 2017; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2012). Meanwhile, there is no agreement regarding the child’s gender. Some studies have found no differences in CPV among gender groups (Calvete, Orue, Gámez-Guadix & Bushman, 2015; Loinaz & De Sousa, 2020; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2012), yet a recent study suggests that gender differences vary depending on the aggression form (Simmons et al., 2018). In terms of age, CPV shows its highest prevalence between the ages of 12 and 17 (Calvete, Orue et al., 2020). However, it can also emerge in childhood or persist into early adulthood (18 to 25 years) (for review, see Simmons et al., 2018). This continuity may be linked to factors such as financial difficulties hindering independence, as well as the persistence of violent dynamics within the parent–child relationship (Ibabe, 2020; Rogers & Ashworth, 2024). To date, few studies have specifically focused on CPV during this stage of development, highlighting the need to generate evidence that can help address this gap in literature.

Regardless of the presence of CPV in society, there is not a clear consensus about its current prevalence (Calvete & Orue, 2016; Contreras & Cano, 2014), mainly due to the variety of definitions (Gámez-Guadix et al., 2012) and disagreements regarding measurement (Calvete et al., 2013). According to research in community and international samples, psychological CPV occurs in a range from 33% to 95.7% in national studies (Calvete et al., 2017; Ibabe & Bentler, 2016) and from 45% to 87.2% of the cases in international studies (Beckmann et al., 2021; Calvete et al., 2018). In addition, findings suggest that physical CPV occurs in 2.6% to 22% of cases in national studies (Contreras et al., 2020; Calvete et al., 2017) and in 5.5% to 47.5% in international studies (Beckmann et al., 2021; Lyons et al., 2015; Margolin & Baucom, 2014).

Even though these studies show high rates of CPV there are still gaps in the research of this growing phenomenon. In addition, most previous studies have centered on family risk factor detection, emphasizing exposure to family violence as a powerful element (Bautista-Aranda et al., 2023; Contreras et al., 2020; Warren et al., 2023). Moreover, harsh discipline strategies, such as physical (Harries et al., 2023) and psychological punishment (Jiménez-Granado et al., 2023; Gámez-Guadix et al., 2012), are also associated with increased CPV. Some research indicates that parents who are physically and psychologically abusive to their children are more likely to experience CPV than those in whom violence does not occur (Beckmann et al., 2021). On the other hand, although little research has attempted to evaluate the individual risk factors of adolescents regarding the development of CPV, there are studies that give us an idea about them. Thus, adolescents’ impulsivity (Loinaz et al., 2020; Rico et al., 2017) and substance use (Calvete, Orue, Gámez-Guadix, Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2015; Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020) have received the most empirical attention. However, there are few studies aiming to identify its protective factors (Beckmann et al., 2021; Loinaz et al., 2023). Even fewer studies have tried to identify factors that can buffer the predictive relation between exposure to family violence and CPV (Contreras et al., 2020; Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020).

Knowing and detecting CPV protective factors while simultaneously working with those that protect youths that are exposed to family violence at home is imperative. The literature shows how mindfulness-based interventions can be beneficial for youths in preventing emotional and behavioral problems (Shorey et al., 2015), improving mental health outcomes (Ortiz & Sibinga, 2017), and being helpful in psychological interventions with perpetrators that have been exposed to violence during their childhood (Ferreira et al., 2019). In addition, mindfulness interventions seem to have a positive effect on the decrease of impulsive (Shorey et al., 2015) and aggressive behaviors in adolescents, thus improving anger management (Vandana & Singh, 2017). Along these lines, the results of a meta-analysis found that mindfulness training interventions generated benefits in terms of the development of dispositional mindfulness (DM) dimensions (Quaglia et al., 2016). Thus, DM dimensions seemed to have a positive effect on the decrease of psychological symptoms in adolescence and youths (Zoogman et al., 2015).

Dispositional mindfulness as a protective factor

DM is the innate ability to consciously attend to the present moment, focusing on sensations, emotions, and thoughts under a non-judging paradigm (Williams et al., 2007), an ability that everyone has to a greater or lesser extent (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). In recent years, there has been growing interest in DM as a protective factor due to its positive impact on mental health in adult (Bergin & Pakenham, 2016), adolescent (Cortazar & Calvete, 2023), and young adult samples (Calvete et al., 2017; Cortazar & Calvete, 2019; Salem & Karlin, 2023). Nevertheless, there are challenges to drawing conclusions about their beneficial role in mental health, mainly given there is no clear consensus on the construct’s definition and evaluation. Some authors define it unidimensionally (Brown & Ryan, 2003), while others consider it a multidimensional construct (Baer et al., 2006; Bishop et al., 2004). However, there is growing consensus over its multifaceted definitions. For instance, Ruth Baer et al. (2006) conducted an exploratory factorial analysis of the five most used tools for DM measurement, suggesting the existence of five distinguishable variables: describing (translating emotional aspects into words); non-judging (accepting sensations, emotions, and thoughts without judgement); acting with awareness (paying attention to perceptions, thoughts, and emotions); observing (disposition to focus on perceptions, thoughts, and emotions); and non-reactivity (preventing getting carried away by thoughts and feelings).

Following the five-factor model, recent studies suggest that the role of each dimension will depend on the psychological problem. Describing was associated with lower internal symptomatology (i.e., anxiety and depression) in young university student samples (Bergin & Pakenham, 2016). Non-judging is associated with lower levels of internalizing symptomatology both at the cross-sectional (Van Son et al., 2015) and the longitudinal level in adult samples, while other studies identify it as contributing to externalizing symptoms in adolescents (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). Acting with awareness has the most benefits toward internalizing symptoms in both adults (Bullis et al., 2014) and adolescents (Ciesla et al., 2012; Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). Furthermore, this dimension presented benefits against externalizing symptomatology in adolescents (Calvete et al., 2017; Cortazar & Calvete, 2019) and in young adult samples (Shorey et al., 2014). Observing showed an ambivalent role depending on the sample type (Aldao et al., 2010). In a general sample, results identified it as prejudicial against internalizing symptomatology in adults (Bullis et al., 2014; Christopher et al., 2012), adolescents, and emerging adults (Royuela-Colomer & Calvete, 2016). Nevertheless, a recent study found that the ability to observe internal emotions benefited the reduction of externalizing symptomatology, as well as aggressive behaviors over time (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). Finally, non-reactivity is negatively associated with internalizing symptoms (Van Son et al., 2015) and externalizing symptoms, reducing physical and psychological aggressions perpetrated in dating violence in young adults’ samples (Shorey et al., 2014), yet is not associated with either internalizing or externalizing symptomatology in studies of adolescents’ samples (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019).

Some studies have assessed the role of DM dimensions in stressful situations. Nerea Cortazar and Esther Calvete (2019) pointed out that describing and non-judging predicted lower internalizing symptomatology when adolescents were exposed to higher levels of stress. Describing was also protective against externalizing symptomatology, following other findings that suggest this ability holds protective potential against stress (Bergin & Pakenham, 2016; Bullis et al., 2014). Alethea Desrosiers et al. (2013) consider it especially important in highly stressful situations. Meanwhile, non-judging, non-reactivity, and acting with awareness did not associate with lower levels of externalizing symptomatology in stressful situations (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). Nevertheless, in the study by Calvete et al. (2017), acting with awareness protected adolescents against externalizing symptomatology in stressful situations. Finally, observing seems to increase internalizing symptomatology in stressful situations (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019).

In spite of the growing evidence centered on the benefits of DM dimensions on mental health, few studies have focused on DM’s potential to prevent externalizing symptoms compared to internalizing ones (Calvete et al., 2017; Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). Moreover, the different facets of DM play a beneficial role in contexts characterized by high levels of stress (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019; Desrosiers et al., 2013). These types of contexts may share features with situations of family violence, suggesting that facets of DM could also play a protective role against CPV in contexts of high exposure to family violence. Few studies have assessed the role of the five DM dimensions, and none of them evaluate the possible relations with CPV aggressive behavior. The main aim of this study was to explore the role of DM dimensions in the relation between exposure to family violence and CPV (physical and psychological) toward mother and father.

The Present Study

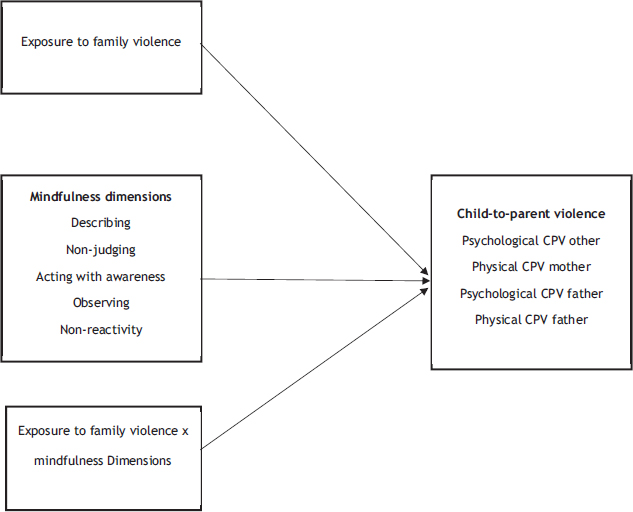

Many studies have tried to identify CPV risk factors (Calvete & Veytia, 2018; Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020). Research identifies exposure to family violence as a potential predictor of CPV (Contreras et al., 2020; Gallego et al., 2019), but there are no studies analyzing the interacting factors. Some DM dimensions have demonstrated a protective role against aggressive behaviors (Calvete et al., 2017; Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). Therefore, the general aim of this study was to assess the role of the five DM dimensions in the relation between exposure to family violence and CPV (physical and psychological) toward mother and father (Figure 1). Taking the previous review into consideration, we first expected to find positive associations between exposure to family violence and physical and psychological CPV toward mother and father. Second, we expected negative associations between all five DM dimensions and all CPV forms toward mothers and fathers. Finally, the five DM dimensions were expected to buffer the relation between exposure to family violence and CPV (physical and psychological) toward mother and father.

Figure 1. Conceptual model.

Method

Participants

The sample was intentional, and it was composed of 415 adolescents and young adults, 311 girls (74.9%), 103 boys (24.8%), and 1 non-binary person (0.2%). The ages of the participants ranked from 18 to 25 years (Mage = 22.54; SDage = 1.72). 97.8% of the participants were from Spain, 0.9% were from other European countries (0.2% Germans, 0.5% Rumanians, and 0.2% Swiss), and the remaining 1.3% were from South America (0.2% from Brazil, 0.7% from Colombia, 0.2% from Uruguay, and 0.2% from Venezuela). Regarding the family situation, 81% of the participants lived with their parental figures, 6.8% with friends, 5.8% with a partner, 1.9% lived alone, and 4.3% did not specify their situation. Finally, regarding employment status, 72.1% were students, 20.7% were employed, 3.8% were unemployed, and 3% did not specify their employment situation.

Measures

Child-to-parent violence. For CPV assessment, the Child-to-Parent Aggression Questionnaire was used (CPAQ; Calvete et al., 2013). This self-report questionnaire is formed by 20 parallel items, 10 items directed to the maternal figure and another 10 to the paternal figure. Questionnaire items measure different physical (seven items) (e.g., “You have kicked or punched”) and psychological CPV (three items) (e.g., “You have insulted or said bad words”) behaviors. The response scale was Likert-type with four response options ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (often, it happened six or more times). CPAQ has shown excellent psychometric properties in Spanish adolescent community samples (Calvete, Morea et al., 2019; Calvete & Orue, 2016) and emerging adults. In this study, Cronbach alpha coefficients were: psychological CPV mother = .72, physical CPV mother = .72, psychological CPV father = .70, physical CPV father = .82.

Dispositional mindfulness. For the assessment of DM, the Spanish version of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ; Cebolla et al., 2012) was administered. This questionnaire was compounded by 39 self-report items that assesses the five DM dimensions: describing (eight items) (e.g., “I am good at finding words to describe my feelings”), non-judging (eight items) (e.g., “I criticize myself for having absurd and irrational ideas”), acting with awareness (eight items) (inverse item; e.g., “I get easily distracted”), observing (eight items) (e.g., “I perceive smells and the aroma of things”), and non-reactivity (seven items) (inverse item; e.g., “I perceive my feelings and emotions without opposing them”). The response scale was Likert type with five response options ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (usually). FFMQ-A has shown acceptable psychometric properties in adolescent and emerging adult community samples (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). In this study, Cronbach alpha coefficients were: .91 for describing; .89 for non-judging; .73 for observing; and .78 for non-reactivity.

Exposure to family violence. Exposure to family violence was assessed using the Exposure to Violence Scale (CEV; Orue & Calvete, 2010). This self-reported questionnaire is compounded by 21 items with a Likert-point scale of five options ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (everyday). This study used the sub-scale of exposure to family violence compound by six items that assesses direct violence (three items) (e.g., “How often did they hit or physically harm you at home”), and indirect violence (three items) (e.g., “How often have you seen a person hitting or physically harming someone at home”). This tool had appropriate psychometric properties in general population samples at the national level (Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020; Orue & Calvete, 2010). The main study used the global index of exposure to family violence, which has a .89 Cronbach alpha coefficient.

Procedure

Data collection and contact with the participants were carried out through social media and QR codes that were published around different universities of Bizkaia. First, participants were informed of the aim and nature of the study. Second, individuals who wanted to participate received an active informed consent form where detailed information about their willingness to participate, anonymity, and data confidentiality was provided, along with a notification that results could be requested at any moment if they so desired it. Thirdly, contact with the researchers was indicated in case they needed to solve any doubts regarding the study. The study was conducted with young adults, with age as the sole exclusion criterion. Accordingly, only participants aged 18 years or older were eligible to participate. Two of the participants rejected the consent for data use (0.48%). The study meets the ethical standards required in psychological research.

Statistical analysis

Correlation analysis among variables of the study and descriptive statistics were analyzed through IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (2012). structural equation model was carried out using version 8.80 of LISREL attending to the robust maximum likelihood method (rml). The paths were analyzed according to the Satorra-Bentler χ2-(S-B χ2) scale and requires the estimation of the variances and covariances. The hypothetical model presented direct paths from exposure to family violence and the five DM dimensions (describing, non-judging, acting with awareness, observing, and non-reactivity) to physical CPV toward mothers, physical CPV toward fathers, psychological CPV toward mothers, and physical CPV toward fathers. The model also included paths from interactions between exposure to family violence and the five dimensions of DM (exposure to family violence X describing, exposure to family violence X non-judging, exposure to family violence X acting with awareness, exposure to family violence X observing, and exposure to family violence X non-reactivity) to physical and psychological CPV toward mothers and fathers. Independent variables were transformed to z punctuations to generate moderation terms (Frazier et al., 2004). The adequation of the model was analyzed according to the fit indexes of the model: NNFI indexes were .90 or higher, RMSEA indexes were .06 or lower, and CFI indexes were .90 or higher; the model fit perfectly (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Results

Descriptive analysis and gender differences

Table 1 shows the correlation coefficients and descriptive analysis among all studied variables. On the one hand, exposure to family violence was positively associated with all CPV forms and with describing and observing dimensions, while negatively with non-judging. On the other hand, non-judging was negatively associated with psychological CPV toward the mother and positively with physical CPV toward the father. Non-reactivity was negatively associated with all CPV forms except for physical CPV toward fathers. Table 2 shows the difference between boys and girls in all the study variables. The results show no gender differences between variables, excluding the acting with awareness dimension, where girls obtained higher scores with a small effect size.

Table 1. Correlations between variables of the study

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

|

1. Exposure to family violence |

1 |

|||||||||

2. Describing |

.15** |

1 |

||||||||

3. Non-judging |

-.10* |

.22** |

1 |

|||||||

4. Acting with awareness |

-.04 |

.33** |

.38** |

1 |

||||||

5. Observing |

.12* |

.33** |

-.13* |

.01 |

1 |

|||||

6. Non-reactivity |

.05 |

.43** |

.28** |

.12* |

.40** |

1 |

||||

7. Psychological CPV mother |

.26** |

-.03 |

-.25** |

-.11* |

.03 |

-.11* |

1 |

|||

8. Physical CPV mother |

.25** |

-.02 |

-.06 |

.00 |

-.10 |

-.13** |

.43** |

1 |

||

9. Psychological CPV father |

.31** |

.01 |

-.18** |

-.09 |

.07 |

-.10* |

.76** |

.35** |

1 |

|

10. Physical CPV father |

.27** |

.01 |

.05 |

.10* |

-.03 |

-.06 |

.25** |

.69** |

.36** |

1 |

Mean |

4.48 |

0.12 |

4.03 |

0.09 |

3.26 |

3.21 |

3.25 |

3.23 |

2.81 |

4.00 |

SD |

3.11 |

0.55 |

2.96 |

0.60 |

0.69 |

0.89 |

0.84 |

0.91 |

0.69 |

4.44 |

Table 2. Descriptive analysis and gender differences

Boys (n=99) |

Girls (n=310) |

||||||

Mean |

SD |

Mean |

SD |

t |

p |

d |

|

1. Exposure to family violence |

3.66 |

4.47 |

4.08 |

4.43 |

-.83 |

.41 |

.09 |

2. Describing |

3.12 |

0.86 |

3.23 |

0.90 |

-1.11 |

.27 |

.12 |

3. Non-judging |

3.25 |

0.93 |

3.22 |

0.90 |

.32 |

.75 |

.03 |

4. Acting with awareness |

3.08 |

0.89 |

3.31 |

0.82 |

-2.39 |

.02 |

.27 |

5. Observing |

3.19 |

0.72 |

3.28 |

0.67 |

-1.19 |

.23 |

.13 |

6. Non-reactivity |

2.90 |

0.75 |

2.78 |

0.68 |

1.52 |

.13 |

.17 |

7. Psychological CPV mother |

4.02 |

3.63 |

4.63 |

2.92 |

-1.71 |

.09 |

.18 |

8. Physical CPV mother |

0.13 |

0.92 |

0.12 |

0.37 |

.28 |

.78 |

.01 |

9. Psychological CPV father |

3.79 |

3.47 |

4.12 |

2.77 |

-.96 |

.34 |

.10 |

10. Physical CPV father |

0.15 |

0.94 |

0.07 |

0.44 |

.79 |

.43 |

.11 |

Model of the study

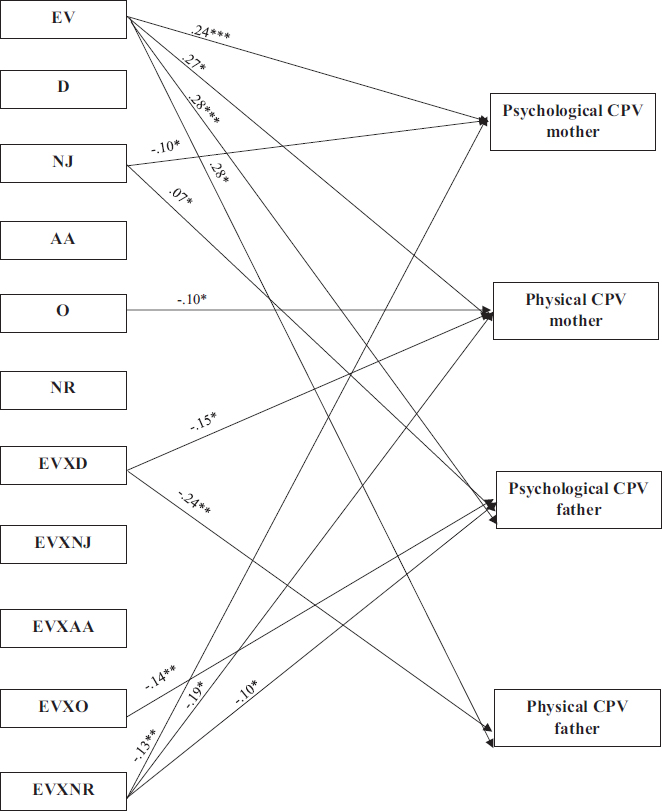

The final model showed excellent Satorra-Bentler adjustment χ2(32, N = 415) = 56.97, RMSEA = .043, (90% CI: .070; .094), NNFI = .96, CFI = .99 y NFI = .97. The model explained 14% of the variance regarding psychological CPV toward mothers, 28% of physical CPV toward mothers, 16% of psychological CPV toward fathers, and 29% of physical CPV toward fathers. Figure 2 shows the significant paths obtained in the parsimonious model. The results showed that exposure to family violence was associated with all CPV forms. Non-judging was negatively associated with psychological CPV toward mothers and positively with psychological CPV toward fathers. Observing was negatively associated with physical CPV toward mothers.

Figure 2. Model of the study

Note. N = 415; EV = exposure to family violence; D = describing; NJ = non-judging; AA = acting with awareness; O = observing; NR = non-reactivity; NFFI =.96, CFI =.99, RMSEA = .043, 90% confidence of interval (.070, .094), standardized paths are shown, *p < .05; **p <.01; ***p <.001.

Three moderation terms were associated with changes in CPV: exposure to family violence X describing was associated with physical CPV toward mothers and fathers. Exposure to family violence X observing was negatively associated with psychological CPV among fathers. Exposure to family violence X non-reactivity was negatively associated with psychological CPV among mothers and fathers and with physical CPV toward mothers.

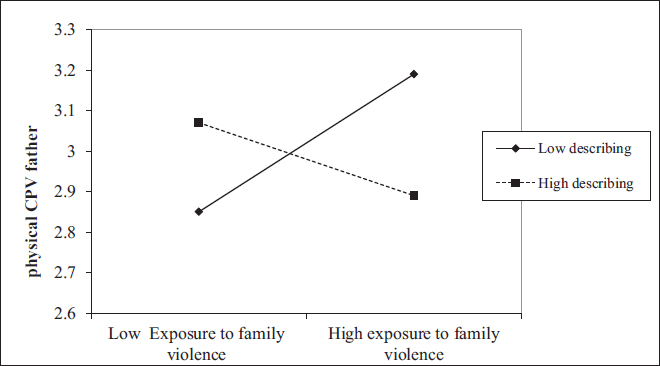

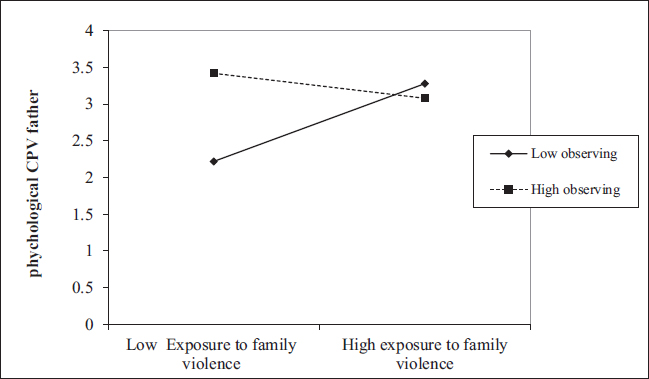

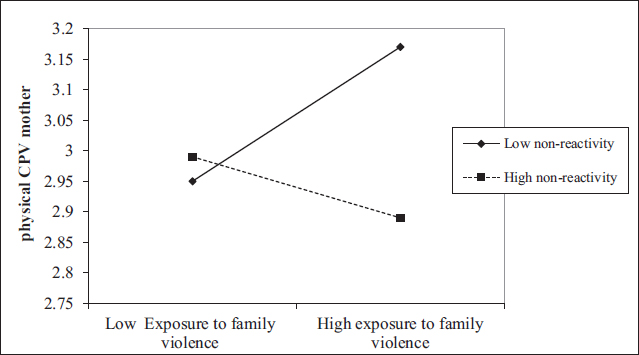

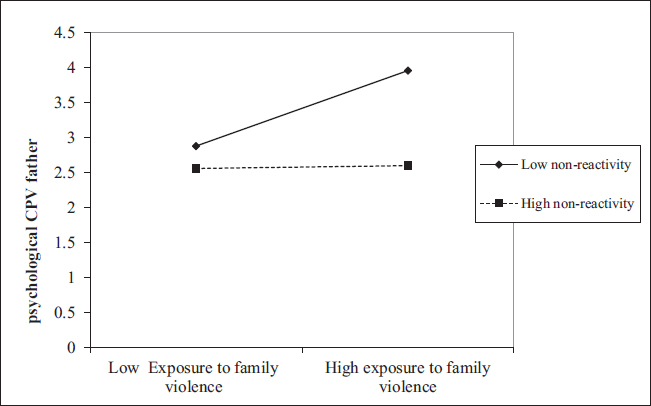

The significant interactions are shown in various figures for their interpretation. Figure 3 shows the structural interaction between exposure to family violence X describing in relation to physical CPV among father. Thus, when the exposure to family violence is high, physical CPV toward fathers increases only when describing abilities are low. The interaction between exposure to family violence X describing in relation with physical CPV toward father was not reflected because the interaction form was similar. Figure 4 shows the association between exposure to family violence X observing and psychological CPV toward fathers. Thus, when exposure to family violence is high and the observing dimension is low, psychological CPV toward fathers increases. Figure 5 indicates the association obtained between exposure to family violence X non-reactivity in relation to physical CPV toward mothers. Thus, when exposure to family violence is high and the levels of non-reactivity are low, physical CPV toward mothers increases. Figure 6 shows the association between exposure to family violence x non-reactivity and psychological CPV toward fathers. Thus, when exposure to family violence is high, and non-reactivity is low, psychological CPV toward fathers increases. The interaction between exposure to family violence X non-reactivity in the relation with psychological CPV toward mothers was not reflected because the interaction form was similar.

Figure 3. Interaction among describing and exposure to family violence for physical CPV father

Figure 4. Interaction among observing and exposure to family violence for psychological CPV father

Figure 5. Interaction among non-reactivity and exposure to family violence for physical CPV mother

Figure 6. Interaction among non-reactivity and exposure to family violence for psychological CPV father

Discussion

Exposure to family violence is a powerful risk factor for CPV (Bautista-Aranda et al., 2023; Gallego et al., 2019; Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020). The aim of this study was to assess the moderating role of the five DM dimensions in the impact of exposure to family violence and psychological and physical CPV toward mothers and fathers. The results showed different roles for each DM dimensions of considering both psychological and physical forms of CPV toward mothers and fathers, both in direct and indirect interaction with exposure to family violence. Observing was associated with lower levels of CPV, whereas non-judging showed an ambivalent role. In addition, some DM dimensions (i.e., describing, observing, and non-reactivity) proved to be protective against CPV for people with high levels of exposure to family violence.

Following previous studies (e.g., Calvete & Orue, 2016; Del Hoyo-Bilbao et al., 2020), exposure to family violence was associated positively with all CPV forms. As previously indicated, there are not many studies that assess protective factors against CPV when there is exposure to family violence, and to our knowledge, none of the studies analyze the role of DM dimensions in that relation. In the present study, DM, in general, was protective against CPV. The results of each of the five DM dimensions are presented and discussed.

First, describing was not related to any CPV form but showed a protective role against physical CPV toward both parents in interaction with exposure to family violence. This result concurred with that of Cortazar and Calvete’s (2019) study, where, even though this dimension did not directly predict changes in behavioral problems, it showed a protective role against aggressive behaviors in stressful situations. Even more, taking previous literature into account (e.g., Bergin & Pakenham, 2016; Desrosiers et al., 2013), this dimension could be important in stressful situations, as it could be an exposure to family violence situation. Therefore, it is possible that a high capacity to put feelings and emotions into words may be associated with better communication skills, greater self-control, and conflict-solving skills, which in turn may reduce CPV responses. In fact, some studies indicated how this capacity is necessary for communication and self-control (Linehan, 1993) and that it could enhance efficient problem-solving at highly stressful times (Bergin & Pakenham, 2016).

Secondly, non-judging had an ambivalent role with CPV. It protects against psychological CPV toward mothers, but it seems to be prejudicial against psychological CPV toward fathers. These results are not easy to explain. On one hand, like in many previous studies (e.g., Bergin & Pakenham, 2016; Ciesla et al., 2012; Van Son et al., 2015), non-judging is shown as a protective dimension, also associated with lower levels of aggressive behavior (Kim et al., 2022). Nevertheless, it seems to have an opposite direction in the case of psychological CPV toward fathers. Some studies indicated that non-judging, partly, implies a lack of negative self-evaluation and a lack of limits on oneself, which can increase externalizing symptomatology (Calvete, 2008; Cortazar & Calvete, 2019; Jones et al., 2016). A possible explanation for this differential pattern may lie in the distinct relational dynamics that adolescents develop with each parental figure, as well as in the moderating role of the adolescent’s gender (Hoskins, 2014). In this regard, these dynamics tend to be established with the family member who traditionally assumes the educational role, which, in most cases, is the mother (Condry & Miles, 2014; Holt, 2016). Social norms around child-rearing continue to attribute primary responsibility for children’s upbringing to mothers, reinforcing their central role in the disciplinary sphere (Rogers & Ashworth, 2024). Consequently, in families characterized by more authoritarian parenting styles, where harsh and violent strategies such as punitive punishment (i.e., physical or psychological) are implemented, there may be a greater likelihood of CPV being directed specifically toward the mother figure (Llorca et al., 2017; Masud et al., 2019; Seijo et al., 2020). Moreover, recent studies have indicated that the non-judging facet may not exert a protective effect specifically in contexts of high adversity. For example, Cortazar and Calvete (2019) found that this dimension did not moderate the relationship between adverse experiences and externalizing symptoms in adolescents. In this regard, some research suggests that certain facets of DM, such as the ability to refrain from judging emotions, thoughts, or sensations, may only be beneficial when accompanied by a conscious and deliberate attitude, such as acting with awareness (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019).

Thirdly, defying expectations, acting with awareness failed to prove to be protective against CPV, neither directly nor in interaction. Numerous investigations showed the benefits of this dimension regarding different psychological problems (e.g., Bergin & Pakenham, 2016; Bränström et al., 2011; Cortazar & Calvete, 2019) and aggressive behaviors perpetrated in dating violence relationships (Shorey et al., 2014). Nevertheless, acting with awareness showed different roles depending on the psychological and behavioral problem (Bullis et al., 2014; Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). Furthermore, recent studies suggest that, so that certain DM dimensions may be beneficial, they require high levels of achievement in other dimensions (Cortazar et al., 2019). For example, Cortazar and Calvete (2019) found that acting with awareness in interaction with non-judging reduced aggressive behaviors over time. In this regard, it could be understood that acting with awareness dimension may only exert its beneficial effects when combined with other facets, such as non-judging (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). Moreover, its impact may vary depending on the specific type of issue being addressed, such as internalizing (i.e., depression or anxiety) or externalizing problems (i.e., aggressive behaviors). Therefore, future studies should analyze the potential interaction between acting with awareness and other dimensions in the specific problem of CPV.

Fourthly, results indicate that the ability to observe internal sensations and emotions is related to lower levels of physical CPV toward mothers. Even though, generally, observing has proved prejudicial against internalizing symptoms in samples without meditation experience (Baer et al., 2008), recent studies indicate its benefits for externalizing problems (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019). Specially, observing diminished rule-breaking and aggressive behaviors (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019; Euler et al., 2017). Moreover, observing also showed a protective role in situations of high exposure to family violence against psychological CPV among fathers. This could be explained, as Cortazar and Calvete (2019) stated, by its relation to empathy and understanding feelings of other people (Jones et al., 2016). Therefore, results suggest that internal observing of one-self’s sensations and recognizing them in stressful situations, such as in those situations in the family environment, could positively influence CPV responses (Deng et al., 2024). In this way, the ability to observe one’s own emotions as well as those of others, combined with the development of empathy (Hosseinian et al., 2019), may contribute to improvements in emotional control and impulsivity (Deng et al., 2024; Galla et al., 2016), thereby reducing the perpetration of aggressive behaviors (Tao et al., 2021). These findings are reflected in contexts where observing emotions has a beneficial effect in reducing psychological aggression among youth exposed to high-violence situations (Sharma et al., 2016).

Finally, even though non-reactivity did not associate directly with any CPV form, it plays a relevant role with regard to psychological CPV toward both parents and physical CPV toward mothers when there is exposure to family violence situations at home. Considering a few studies that had analyzed the protective role of the non-reactivity dimension against externalizing symptomatology in stressful situations (Cortazar & Calvete, 2019; Van Son et al., 2015), results indicate that different patterns follow this dimension. Whereas previous studies didn’t find significant relationships, in the present study those people in this study who had greater non-reactivity emotions perpetrated less CPV, regardless of exposure to high levels of violence at home. Therefore, data suggest that this dimension plays an important role when the form of perpetrated violence is directed to people with strong emotional ties, as is the case of the child-to-parent relation; this may help to prevent the reproduction of the violent behaviors previously visualized.

Limitations and future research

This research dealt with certain limitations that should be considered in future endeavors. First, the present study employed a cross-sectional design, which limits the ability to establish causal or temporal relationships between exposure to family violence and DM. Future research would benefit from using longitudinal designs to explore the directionality and stability of these associations over time. Second, this study did not assess prior mindfulness instruction or practice in participants or their parents. Future research should consider this variable, as it may influence levels of DM. In this sense, it would also be especially relevant to assess DM in parental figures, as their own mindfulness traits may influence the dynamics of child-to-parent violence. Third, this study addresses sensitive topics through online questionnaires, which may have led to a social desirability bias in participants’ responses. Fourth, the sample is composed predominantly of individuals residing in Spain, which introduces a geographical and cultural bias. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted within the specific sociocultural context of Spain and cannot be readily generalized to populations from other cultural backgrounds. Future research should aim to replicate these findings across different countries and cultural contexts. Fifth, regarding sampling, an intentional sampling strategy was used, aligned with the study’s objectives and facilitated through social media dissemination, allowing efficient access to young adults. However, this approach may limit the representativeness of the sample, potentially favoring individuals with greater digital access or interest in psychological topics. Future studies are encouraged to employ more probabilistic or complementary sampling methods to enhance the generalizability of findings. Sixth, another limitation of this study is that it did not examine the relationship with the parental figures or the potential moderating effect of the adolescent’s gender. As these variables may influence family dynamics (Hoskins, 2014), future research should take them into account to better understand their role in the relationship between DM and CPV. Finally, another limitation of this study is that it did not examine the potential interaction between the different facets of DM. Future research should explore how the combination of specific facets may influence CPV outcomes, as some traits might only be beneficial when they operate together.

In spite of the mentioned limitations, this study presented some strengths to consider. To our knowledge, there are few studies that have analyzed the protective effects of DM from a multidimensional perspective (considering the five DM dimensions) in relation to externalizing symptomatology and none against CPV. This study contributes as preliminary data regarding the role of DM in CPV, adding information about new protective factors. Thus, DM seems to have a relevant role against CPV, especially in situations of exposure to violence in the family environment. Therefore, it is of great relevance to carry out investigations with longitudinal designs that can support these results, with the final purpose of developing mindfulness-based interventions that especially focus on increasing CPV protective dimensions.

Conclusion and practical and clinical implications

This study successfully achieved its general objective by examining the moderating role of different dimensions of DM in the relationship between exposure to family violence and CPV, both physical and psychological, toward both parents. The findings provide empirical evidence of the differentiated effects of mindfulness, highlighting its potential as a protective factor in highly conflictive family contexts. Among the most relevant results, a consistent association was found between exposure to family violence and all forms of CPV. The dimensions of describing, observing, and non-reactivity demonstrated protective effects in the context of high exposure to family violence, while non-judging showed an ambivalent effect, and acting with awareness did not show significant effects. These findings underscore the importance of considering both context and the specificity of each mindfulness facet when designing interventions.

The results of this study have important implications for the development of preventive and clinical interventions aimed at reducing CPV. First, the consistent association between exposure to family violence and the different forms of CPV reaffirms the need to address the family environment in intervention efforts. Moreover, the moderating effects of the describing, observing, and non-reactivity facets suggest that enhancing the ability to pay attention to emotions and thoughts, verbalize emotional experiences, and avoid impulsive reactions may be particularly relevant for adolescents exposed to family violence, as these skills can help reduce the likelihood of violent behavior toward parents.

Therefore, preventive and clinical programs targeting CPV could benefit from incorporating mindfulness-based strategies, especially in family contexts characterized by high levels of conflict. The integration of such components would not only address violent behaviors but also equip adolescents with internal resources to manage intense emotional experiences resulting from adverse family environments. A critical reflection on the usefulness of each mindfulness dimension in vulnerable populations may lead to more precise and effective intervention programs.

In conclusion, this study not only advances understanding of the mechanisms involved in CPV in contexts of family violence but also provides a solid foundation for the development of more integrated clinical and preventive interventions. These should be sensitive to the adolescent’s context and focused on strengthening internal resources that contribute to the reduction of CPV.

Funding

This research was supported by grants from the project (Agencia Estatal de Investigación - Ministry of Science and Innovation of Spain), PID2022-139727OA-I00 funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 - FEDER, UE, the Basque Government (IT1532-22), the University of Deusto, grant number [FPI UD_2022_09] [FPI UD_2022_09] and supported by the PROEMO Network (RED2022-134247-T, funded by MCIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033).

References

Aldao, Amelia; Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan, & Schweizer, Susanne. (2010). Emotion-regulation strategies across psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 217–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.004

Baer, Ruth A.; Smith, Gregory T.; Hopkins, Jaclyn; Krietemeyer, Jennifer, & Toney, Leslie. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

Baer, Ruth A.; Smith, Gregory T.; Lykins, Emily; Button, Daniel; Krietemeyer, Jennifer; Sauer, Shannon; Walsh, Erin, & Williams, J. Mark W. (2008). Construct validity of the five-facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003

Bautista-Aranda, Nazaret; Contreras, Lourdes, & Cano-Lozano, M. Carmen. (2023). Exposure to violence during childhood and child-to-parent violence: The mediating role of moral disengagement. Healthcare, 11(10), 1402. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101402

Beckmann, Laura; Bergmann, Marie C.; Fischer, Franziska, & Mößle, Thomas. (2021). Risk and protective factors of child-to-parent violence: A comparison between physical and verbal aggression. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), NP1309–1334NP. http://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517746129

Bergin, Adele J., & Pakenham, Kenneth I. (2016). The stress-buffering role of mindfulness in the relationship between perceived stress and psychological adjustment. Mindfulness, 7(4), 928–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0532-x

Bishop, Scott R.; Lau, Mark; Shapiro, Shauna; Carlson, Linda; Anderson, Nicole D.; Carmody, James; Segal, Zindel V.; Abbey, Susan; Speca, Michael; Velting, Drew, & Devins, Gerald. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 11(3), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bph077

Branje, Susan. (2018). Development of parent–adolescent relationships: Conflict interactions as a mechanism of change. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 171–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12278

Bränström, Richard; Duncan, Larissa G., & Moskowitz, Judith. (2011). The association between dispositional mindfulness, psychological well-being, and perceived health in a Swedish population-based sample. British Journal of Health Psychology, 16(2), 300–316. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910710X501683

Brown, Kirk W., & Ryan, Richard M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Bullis, Jaqueline R.; Bøe, Hans J.; Asnaani, Anu, & Hofmann, Stefan G. (2014). The benefits of being mindful: Trait mindfulness predicts less stress reactivity to suppression. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 45, 57–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbtep.2013.07.006

Calvete, Esther. (2008). Justification of violence and grandiosity schemas as predictors of antisocial behavior in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(7), 1083–1095. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9229-5

Calvete, Esther; Fernández-González, Liria; Orue, Izaskun, & Little, Tood. (2018). Exposure to family violence and dating violence perpetration in adolescents: Potential cognitive and emotional mechanisms. Psychology of Violence, 8(1), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000076

Calvete, Esther; Gámez-Guadix, Manuel; Orue, Izaskun; González-Diez, Zahira; de Arroyabe, Elena L.; Sampedro, Rafael; Pereira, Roberto; Zubizarreta, Anik, & Borrajo, Erika. (2013). Brief report: The Adolescent Child-to-Parent Aggression Questionnaire: An examination of aggressions against parents in Spanish adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1077–1081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.017

Calvete, Esther; Morea, Aida, & Orue, Izaskun. (2020). The role of dispositional mindfulness in the longitudinal associations between stressors, maladaptive schemas, and depressive symptoms in adolescents. Mindfulness, 10(3), 547–558. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1000-6

Calvete, Esther, & Orue, Izaskun. (2016). Violencia filio-parental: Frecuencia y razones para las agresiones contra padres y madres. Psicología Conductual, 24(3), 481–495. https://www.behavioralpsycho.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/06.Calvete_24-3oa-2.pdf

Calvete, Esther; Orue, Izaskun; Fernández-González, Liria; Chang, Rong, & Little, Tood D. (2019). Longitudinal trajectories of child-to-parent violence through adolescence. Journal of Family Violence, 35(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-019-00106-7

Calvete, Esther; Orue, Izaskun; Gámez-Guadix, Manuel, & Bushman, Brad J. (2015). Predictors of child-to-parent aggression: A 3-year longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 51(5), 663–676. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039092

Calvete, Esther; Orue, Izaskun; Gámez-Guadix, Manuel; Del Hoyo-Bilbao, Joana, & De Arroyabe, Elena. (2015). Child-to-parent violence: An exploratory study of the roles of family violence and parental discipline through the stories told by Spanish children and their parents. Violence and Victims, 30(6), 935–947. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.VV-D-14-00105

Calvete, Esther; Orue, Izaskun, & González-Cabrera, Joaquín. (2017). Violencia filio-parental: Comparando lo que informan los adolescentes y sus progenitores. Revista de Psicología Clínica con Niños y Adolescentes, 4(1), 9–15. https://www.revistapcna.com/sites/default/files/16-08.pdf

Calvete, Esther; Orue, Izaskun, & Sampedro, Rafael. (2011). Violencia filio-parental en la adolescencia: Características ambientales y personales. Infancia y Aprendizaje, 34(3), 349–363. https://doi.org/10.1174/021037011797238577

Calvete, Esther, & Veytia, Marcela. (2018). Adaptación del cuestionario de violencia filio-parental en adolescentes mexicanos. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 50(1), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.14349/rlp.2018.v50.n1.5

Cebolla, Ausiàs; García-Palacios, Azucena; Soler, Joaquim; Guillen, Verónica; Banos, Rosa María, & Botella, Cristina. (2012). Psychometric properties of the Spanish validation of the Five Facets of Mindfulness Questionnaire (FFMQ). The European Journal of Psychiatry, 26(2), 118–126. https://doi.org/10.4321/S021361632012000200005

Christopher, Michael; Neuser, Ninfa J.; Michael, Paul G., & Baitmangalkar, Ashwini. (2012). Exploring the psychometric properties of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire. Mindfulness, 3(2), 124–131. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-011-0086-x

Ciesla, Jeffrey A.; Reilly, Laura C.; Dickson, Kelsey S.; Emanuel, Amber S., & Updegraff, John A. (2012). Dispositional mindfulness moderates the effects of stress among adolescents: Rumination as a mediator. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41(6), 760–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2012.698724

Condry, Rachel, & Miles, Caroline. (2014). Adolescent to parent violence: Framing and mapping a hidden problem. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 14(3), 257–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895813500155

Contreras, Lourdes, & Cano, M. Carmen. (2014). Family profile of young offenders who abuse their parents: A comparison with general offenders and non-offenders. Journal of Family Violence, 29(8), 901–910. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9637-y

Contreras, Lourdes; León, Samuel, & Cano-Lozano, M. Carmen. (2020). Socio-cognitive variables involved in the relationship between violence exposure at home and child-to-parent violence. Journal of Adolescence, 80(1), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.01.017

Cortazar, Nerea, & Calvete, Esther. (2019). Dispositional mindfulness and its moderating role in the predictive association between stressors and psychological symptoms in adolescents. Mindfulness, 10(10), 2046–2059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01175-x

Cortazar, Nerea, & Calvete, Esther. (2023). Longitudinal associations between dispositional mindfulness and addictive behaviors in adolescents. Adicciones, 35(1), 57–66. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.1598

Cortazar, Nerea; Calvete, Esther; Fernández-González, Liria, & Orue, Izaskun. (2019). Development of a short form of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire–Adolescents for children and adolescents. Journal of personality assessment, 102(5), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2019.1616206

Del Hoyo-Bilbao, Joana; Orue, Izaskun; Gámez-Guadix, Manuel, & Calvete, Esther. (2020). Multivariate models of child-to-mother violence and child-to-father violence among adolescents. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 12(1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2020a2

Deng, Xinmei; Lin, Mingping, & Li, Xiaoling. (2024). Mindfulness meditation enhances interbrain synchrony of adolescents when experiencing different emotions simultaneously. Cerebral Cortex, 34(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhad474

Desrosiers, Alethea; Klemanski, David H., & Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan. (2013). Mapping mindfulness facets onto dimensions of anxiety and depression. Behavior Therapy, 44(3), 373–384. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.02.001

Euler, Felix; Steinlin, Célia, & Stadler, Christina. (2017). Distinct profiles of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescents: Associations with cognitive and affective empathy. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 11(1), 2–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-016-0141-4

Ferreira, Maria N. X.; Hino, Paula; Taminato, Mônica, & Fernandes, Hugo. (2019). Care of perpetrators of repeat family violence: An integrative literature review. Acta Paulista De Enfermagem, 32(3), 334–340. http://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0194201900046

Frazier, Patricia A.; Tix, Andrew P., & Barron, Kenneth E. (2004). Testing moderator and mediator effects in counseling psychology research. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 51(2), 115–134. http://doi.org./10.1037/0022-0167.51.2.157

Galla, Brian M.; Kaiser-Greenland, Susan, & Black, David S. (2016). Mindfulness training to promote self-regulation in youth: Effects of the Inner Kids program. Mindfulness, 1(3), 137–144. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12671-010-0011-8

Gallego, Raquel; Novo, Mercedes; Fariña, Francisca, & Arce, Ramón. (2019). Child-to-parent violence and parent-to-child violence: A meta-analytic review. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 11(2), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2019a4

Gámez-Guadix, Manuel; Jaureguizar, Joana; Almendros, Carmen, & Carrobles, José A. (2012). Estilos de socialización familiar y violencia de hijos a padres en población española. Psicología Conductual/Behavioral Psychology, 20(3), 585–602. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1268707028?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true&sourcetype=Scholarly%20Journals

Harries, Travis; Curtis, Ashlee; Valpied, Olvia; Baldwin, Ryan; Hyder, Shannon, & Miller, Peter. (2023). Child-to-parent violence: Examining cumulative associations with corporal punishment and physical abuse. Journal of Family Violence, 38(7), 1317–1324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00437-y

Holt, Amanda. (2016). Adolescent-to-parent abuse as a form of “domestic violence”: A conceptual review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 17(5), 490–499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838015584372

Hoskins, Donna H. (2014). Consequences of parenting on adolescent outcomes. Societies, 4(3), 506–531. https://doi.org/10.3390/soc4030506

Hosseinian, Simin; Nooripour, Roghieh, & Afrooz, Gholam A. (2019). Effect of mindfulness-based training on aggression and empathy of adolescents at the juvenile correction and rehabilitation center. Journal of Research & Health, 9(6), 505–515. https://doi.org/10.32598/jrh.9.6.505

Hu, Li-Tze, & Bentler, Peter M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6, 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Ibabe, Izaskun. (2020). A systematic review of youth-to-parent aggression: Conceptualization, typologies, and instruments. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 577757. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.577757

Ibabe, Izaskun, & Bentler, Peter M. (2016). The contribution of family relationships to child-to-parent violence. Journal of Family Violence, 31(2), 259–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9764-0

IBM Corp. (2012). IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0. IBM Corp.

Jiménez-Granado, Aitor; Del Hoyo-Bilbao, Joana, & Fernández-González, Liria. (2023). Interaction of parental discipline strategies and adolescents’ personality traits in the prediction of child-to-parent violence. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 15(1), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2023a5

Jones, Sussane M.; Bodie, Graham D., & Hughes, Sam D. (2016). The impact of mindfulness on empathy, active listening, and perceived provisions of emotional support. Communication Research, 46(6), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650215626983

Kabat-Zinn, Jon. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(2), 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy/bpg016

Kim, El-Lim; Gentile, Douglas A.; Anderson, Craig A., & Barlett, Christopher P. (2022). Are mindful people less aggressive? The role of emotion regulation in the relations between mindfulness and aggression. Aggressive Behavior, 48(6), 546–562. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.22036

Linehan, Marsha M. (1993). Skills training manual for treating borderline personality disorder. Guilford Press.

Llorca, Anna; Richaud, María C., & Malonda, Elisabeth. (2017). Parenting styles, prosocial, and aggressive behavior: The role of emotions in offender and non-offender adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1246. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01246

Loinaz, Ismael; Barboni, Lucía, & De Sousa, Ava M. (2020). Diferencias de sexo en factores de riesgo de violencia filio-parental. Annals of Psychology, 36(3), 408–417. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.428531

Loinaz, Ismael, & De Sousa, Ava M. (2020). Assessing risk and protective factors in clinical and judicial child-to-parent violence cases. The European Journal of Psychology Applied to Legal Context, 12(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.5093/ejpalc2020a5

Loinaz, Ismael; Irureta, Maialen, & San Juan, César. (2023). Child-to-parent violence specialist and generalist perpetrators: Risk profile and gender differences. Healthcare, 11(10), 1458. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11101458

Lyons, Jennifer; Bell, Tessa; Fréchette, Sabrina, & Romano, Elisa. (2015). Child-to-parent violence: Frequency and family correlates. Journal of Family Violence, 30(6), 729–742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9716-8

Margolin, Gayla, & Baucom, Brian R. (2014). Adolescents’ aggression to parents: Longitudinal links with parents’ physical aggression. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(5), 645–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.05.008

Masud, Hamid; Ahmad, Muhammad S.; Cho, Ki W., & Fakhr, Zainab. (2019). Parenting styles and aggression among young adolescents: A systematic review of literature. Community Mental Health Journal, 55(6), 1015–1030. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00400-0

O’Hara, Karey; Duchschere, Jennifer E.; Beck, Connie J. A., & Lawrence, Erika. (2017). Adolescent-to-parent violence: Translating research into effective practice. Adolescent Research Review, 2(3), 181–198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-016-0051-y

Ortiz, Robin, & Sibinga, Erica M. (2017). The role of mindfulness in reducing the adverse effects of childhood stress and trauma. Children, 4(3), 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/children4030016

Orue, Izaskun, & Calvete, Esther. (2010). Elaboración y validación de un cuestionario para medir la exposición a la violencia en infancia y adolescencia. International Journal of Psychology and Psychological Therapy, 10(2), 279–292. https://www.ijpsy.com/volumen10/num2/262/elaboracin-y-validacin-de-un-cuestionario-ES.pdf

Pereira, Roberto; Loinaz, Ismael; Del Hoyo Bilbao, Joana; Arrospide, Josu; Bertino, Lorena; Calvo, Ana; Montes, Yadira, & Gutiérrez, Mari M. (2017). Proposal for a definition of filio-parental violence (SEVIFIP). Papeles Del Psicólogo, 38(3), 216–223. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2017.2839

Quaglia, Jordan T.; Braun, Sarah E.; Freeman, Sara P.; McDaniel, Michael A., & Brown, Kirk W. (2016). Meta-analytic evidence for effects of mindfulness training on dimensions of self-reported dispositional mindfulness. Psychological Assessment, 28(7), 803–818. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000268

Rico, Eva; Rosado, Jaime, & Cantón-Cortés, David. (2017). Impulsiveness and child-to-parent violence: The role of aggressor’s sex. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 20(e15), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/sjp.2017.15

Rogers, Michaela M., & Ashworth, Charlotte. (2024). Child-to-parent violence and abuse: A scoping review. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 25(4), 3285–3298. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380241246033

Royuela-Colomer, Estibaliz, & Calvete, Esther. (2016). Mindfulness facets and depression in adolescents: Rumination as a mediator. Mindfulness, 7(5), 1092–1102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-016-0547-3

Salem, Maha Ben, & Karlin, Nancy J. (2023). Dispositional mindfulness and positive mindset in emerging adult college students: The mediating role of decentering. Psychological Reports, 126(2), 601–619. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294121106705

Seijo, Dolores; Vázquez, María J.; Gallego, Raquel; Gancedo, Yurena, & Novo, Mercedes. (2020). Adolescent-to-parent violence: Psychological and family adjustment. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 573728. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.573728

Sharma, Manoj K.; Sharma, Mahendra P., & Marimuthu, P. (2016). Mindfulness-based program for management of aggression among youth: A follow-up study. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 38(3), 213–216. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.183087

Shorey, Ryan C.; Anderson, Scott, & Stuart, Gregory L. (2015). The relation between trait mindfulness and aggression in men seeking residential substance use treatment. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 30(10), 1633–1650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514548586

Shorey, Ryan C.; Seavey, Amanda E.; Quinn, Emily, & Cornelius, Tara L. (2014). Partner-specific anger management as a mediator of the relation between mindfulness and female perpetrated dating violence. Psychology of Violence, 4(1), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033658

Simmons, Melanie; McEwan, Troy E.; Purcell, Rosemary, & Ogloff, James R. (2018). Sixty years of child-to-parent abuse research: What we know and where to go. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 38, 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.11.001

Tao, Sisi; Li, Jianbin; Zhang, Mengge; Zheng, Pengjuan; Lau, Eva Y. H.; Sun, Jin, & Zhu, Yuxin. (2021). The effects of mindfulness-based interventions on child and adolescent aggression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 12(6), 1301–1315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01570-9

Van Son, Jenny; Nyklíček, Ivan; Nefs, Giesje; Speight, Jane; Pop, Victor J., & Pouwer, François. (2015). The association between mindfulness and emotional distress in adults with diabetes: Could mindfulness serve as a buffer? Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 38(2), 251–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-014-9592-3

Vandana, Mamta, & Singh, Singh. (2017). Understanding aggression among youth in the context of mindfulness. Indian Journal of Health and Wellbeing, 8(11), 1377–1379. https://iahrw.org/product/understanding-aggression-among-youth-in-the-context-of-mindfulness/

Warren, Amy; Blundell, Barbara; Chung, Donna, & Waters, Rebecca. (2023). Exploring categories of family violence across the lifespan: A scoping review. Trauma, violence, & abuse, 25(2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380231169486

Williams, Mark; Teasdale, John; Segal, Zindel, & Kabat-Zinn, Jon. (2007). The mindful way through depression. The Guilford Press.

Zoogman, Sarah; Goldberg, Simon B.; Hoyt, William T., & Miller, Lisa. (2015). Mindfulness interventions with youth: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 6(2), 290–302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01175-x

Sara Rodriguez-Gonzalez

Her work focuses on the study of child-to-parent violence, both offline and online (Cyber-CPV), its risk and protective factors, and intrafamilial dynamics mediated by ICTs, combining qualitative and quantitative methods to explore these phenomena. She has also contributed to research on the mental health of transgender and nonbinary youth.

sara.r@deusto.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3312-2157

Nerea Cortazar

Her research trajectory has encompassed various lines, focusing primarily on the protective effects of trait mindfulness against internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Additionally, they have conducted multiple studies on different types of violence, all of which have been carried out with adolescent and youth populations.

nerea.cortazar@deusto.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9286-6818

Joana Del Hoyo-Bilbao

Her research trajectory focuses on the study of violence, both offline and online, particularly among youth and families. Her main line of research centers on child-to-parent violence, examining both its risk and protective factors. In addition, she has conducted various studies addressing different forms of violence within adolescent and youth populations.

joana.delhoyo@deusto.es

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0009-7215

Formato de citación

Rodriguez-Gonzalez, Sara; Cortazar, Nerea & Del Hoyo-Bilbao, Joana. (2025). Exposure to family violence and child-to-parent violence: dispositional mindfulness as a protective factor. Quaderns de Psicologia, 27(3), e2176. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.2176

Historia editorial

Recibido: 24-05-2024

1ª revisión: 01-14-2025

Aceptado: 23-05-2025

Publicado: 30-12-2025