Quaderns de Psicologia | 2025, Vol. 27, Nro. 2, e2158 | ISSN: 0211-3481 |

https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.2158

https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.2158

Work Identity, Meaning and Meaningfulness of Work: Brazilian Women Immigrants in the USA

Identidad laboral, significado y significado del trabajo: mujeres brasileñas inmigrantes en Estados Unidos

Silvana Curvello de Cerqueira Campos

Sônia Maria Guedes Gondim

Yuri Sá Oliveira Sousa

Universidade Federal da Bahia

Ligia Carolina Oliveira-Silva

Universidade Federal de Uberlândia

Abstract

Objective: To analyze the narratives about the identity, meaning and meaningfulness of the work of women who interrupt their professional lives to accompany their husbands who immigrate to work in another country. Method: Qualitative and longitudinal study with 12 Brazilian women, wives of immigrants, residing in the United States of America (USA), who were interviewed at four different times. Data Analysis: Lexical analysis supported by the Iramuteq software. Results and Conclusions: In general, the participating wives rebuilt their work identity, meaning of work and meaningfulness of work, as they needed to adapt to a new country and to manage the consequences caused by the pandemic, restructuring professional plans and activity routines. Additionally, this study contributes to the knowledge of gender, work, and family by showing how the process of immigration for career purposes remains gendered, as findings evidence that women disproportionately shoulder the burden of geographic relocation

Keywords: Immigration; Work; Meaning of work; Meaningfulness of work; Work identity

Resumen

Objetivo: Analizar las narrativas sobre la identidad, significado y significación del trabajo de mujeres que interrumpen su vida profesional para acompañar a sus maridos que emigran a trabajar a otro país. Método: Estudio cualitativo y longitudinal con 12 mujeres brasileñas, esposas de inmigrantes, residentes en los Estados Unidos de América (EE.UU.), que fueron entrevistadas en cuatro momentos diferentes. Análisis de Datos: Análisis léxico apoyado en el software Iramuteq. Resultados y Conclusiones: En general, las esposas participantes reconstruyeron su identidad laboral, sentido del trabajo y sentido del trabajo, al necesitar adaptarse a un nuevo país y gestionar las consecuencias provocadas por la pandemia, reestructurando planes profesionales y rutinas de actividades. Además, este estudio contribuye al conocimiento sobre género, trabajo y familia al mostrar cómo el proceso de inmigración con fines profesionales sigue estando diferenciado por género, ya que los hallazgos evidencian que las mujeres soportan desproporcionadamente la carga de la reubicación geográfica.

Palavras-chave: Inmigración; Trabajo; Significado del trabajo; Significado del trabajo; Identidad laboral

Introduction

Seeking mostly better living conditions, women have always participated in migratory processes and often in significant numbers (Massey et al., 1993; Morokvasic, 1984), but lately the feminization of migrations is gaining more and more prominence (Castro, 2021). Currently, according to data from the United Nations Organizations (UN) (2021), women account for approximately half of the 272 million (47.9%) people who live and work outside their home/origin countries. Further data indicate that the US has been the main destination for immigrants since 1970 (International Organization for Migration [IOM], 2021). With a population of 327.2 million inhabitants, the country has 44.44 million of immigrants, which is equivalent to 13.6% of their total population.

However, the literature reveals that, worldwide, men outnumber women in international missions (Gherlone, 2019). A study with hetero-affective families concluded the experience is usually more challenging when women are responsible for immigration in the family (Jinnah, 2017), as they face more difficulties in adjusting to the work context, especially when the spouse is not involved. Cultural restrictions increase their vulnerability in an aggressive context of international mobility where men’s adaptation to cultural, social and organizational rules is usually more standardized, with women having the role of accompanying their husbands and often abandoning their careers if necessary (Américo, 2017). Therefore, migration decision usually contains at least some negotiation. Joyce P. Jacobsen and Laurence M. Levin (2000), for example, suggest that although a higher-earning spouse may have a bargaining advantage, migration is best represented as “intrahousehold bargaining”. Like other decisions relevant to work/family roles, migration can reveal patterns of power in marital relationships (Zvonkovic et al., 1994).

When accompanying their male partners who migrate for work, women who abandon their professional lives in their countries of origin need to give new meaning to their relationship with work in this new territory, which generates countless tensions (Bertoldo, 2018). These new experiences can vary depending on whether those women find new jobs. Moreover, as time progresses in the foreign country, there will be some change in how work starts to be reflected in the lives of each woman.

The “wife”, so to speak, faces a new transcultural context often alone, unlike the “husband”, who is usually more supported by the bonds established in the new work context (Aizawa & de Azevedo, 2022). Unfortunately, gender was largely ignored in the immigration literature for a while, as women were subsumed under the category of family migration so that they were treated more as migrants’ wives than female migrants (Boyd, 1989). The patriarchal model of gender/family relations assumed that the true migrant was, naturally, a male in search of economic betterment, placing women in the position of merely accompanying family (Houstoun et al., 1984).

With more women entering the job market in several cultural and class contexts, when there is the possibility of a relocation experience for one spouse, it often represents a career interruption for the accompanying spouse, being intuitive to attest that women workers are less willing to accept job transfers than their male counterparts, even if they are in a similar professional and family situation as them (e.g., Bielby & Bielby, 1992). Role theory has been used to explain these decisions and, more generally, family decision-making. In the traditional conceptualization of gender roles, power and decision-making revert legitimately to men, being women more oriented towards the family (Shihadeh, 1991). Gender-role theory predictions are supported by studies that found that women are more likely to hold back their own career opportunities for the sake of their husbands rather than vice versa, even if they have higher levels of human capital and labor force attachment (Bielby & Bielby, 1992).

Therefore, women are often disadvantaged in family migration decisions, being more likely to move with a spouse despite personal economic losses (Mincer, 1978). Even couples who intend to compromise over career and relocation decisions reproduce a male-leader, female-follower pattern (Challiol & Mignonac, 2005). Consequently, women disproportionately absorb the costs of moving for their husbands’ career opportunities or forgo building their own careers altogether.

Unfortunately, gendered migration has been shown to account for women’s nonlinear work histories (Han & Moen, 1999) and underrepresentation in high-power positions (Wolfinger et al., 2009). As a reflection of the gender pay gap, in most two-earner families, husbands out-earn wives (Bertrand et al., 2015). Although modern times are characterized by an apparent “rejection” or questioning of traditional gender norms and, with an increase in public discussion on how men and women should behave in an egalitarian manner, women continue to be socialized to demonstrate concern for others, selflessness, and sensitivity (Rudman & Phelan, 2008). As a consequence, women (as spouses of employees) tend to accept the subordinate role of a tied mover, whereas men perceive relocation as a career sacrifice (Ullrich et al., 2015).

The immigration process for families usually involves several struggles and concerns. The feeling of strangeness in the new country, for instance, is explained by the uprooting, as entering another country requires the incorporation of new social rules, increasing the distance from the standards of their culture of origin (Bastos, 2020). It applies to the workplace context in case of a new job.

Evidence suggests that cultural uprooting might contribute to mental disorders among immigrants (Hiller & McCaig, 2007). In addition to being uprooted, arriving in a new country is unavoidably marked by a cultural shock. Defined as the social and physical impact that a new environment generates on the individual, this event refers to the psychological disorientation generated by the inability to understand key social and environmental aspects of another cultural and life context (Winkelman, 1994).

Uncertainty in the face of an unfamiliar environment provided by the immigration process can enhance anxiety and stress, with impacts on well-being and health. The experience is surrounded by tensions in the process of rebuilding a new life far away from family members and loss of identity links (Morokvasic, 1984). One of these links is the work identity, which maintains a close relationship with other types of social identities. Professional identity, for instance, is built on the relationship established with a professional group to which one belongs or has as a reference, which might be relatively stable throughout the career (Gjerde & Alvesson, 2020; Rossit et al., 2018). Professional identity is also the result of sharing knowledge and norms established by training, certification and professional regulation (Reeves, 2016).

However, work identity is not limited to professional identity, being broader than affiliation to a career (Bentley et al., 2019). Although there are interrelationships between work and professional identity, in this study, the focus is on work identity, since the objective is to understand the changes that may occur in women’s work identities who migrate to accompany their husbands, regardless of previous professional career experiences.

Work identity represents a set of beliefs, invested with affections about work as a human activity and part of the self-concept (Byron & Crafford, 2012), supported by the meaningfulness and meaning attributed to work (Reis & Puente-Palácios, 2019). From our perspective, building a work identity in a new country requires replacing work meaningfulness and meaning. The first concept involves a subjective work experience, and the second incorporates a new work socialization process.

The meaning of work would be the set of beliefs about the image of work influenced by collective experiences shared in a specific historical, economic and social context, being incorporated throughout the socialization process (Gjerde & Alvesson, 2020). The transformations that the meaningfulness and meaning undergo are constructed through a dialectical relationship with reality. That is, the diversity of meaning and meaningfulness of work permeates the way in which the worker understands and attributes value to his work. Social and personal factors contribute to the revision of meaningfulness and meaning, which could occur in case of a change of country (Rossit et al., 2018).

Within this scenario, one cannot fail to address the crisis brought by COVID-19, which affected the whole world’s population, but particularly immigrants (Bastos, 2020). Although men with stable ties did not suffer so much negative impacts, the pandemic considerably affected immigrant women who were looking for work, which may have had repercussions on their work identity and meanings attributed to work (Cazarotto & Sindelar, 2020).

Therefore, this research aimed to answer the following questions: 1) How affected is the work identity of women who give up their job to accompany a husband who migrates for professional reasons?; 2) Would this work identity be rebuilt or replaced, or would it be based on new meaningfulness and meaning of work? 3) How does the length of time living in the new country interfere with the identity, meaningfulness and meaning of work? 4) Would there be differences between women with paid and non-paid work in relation to work identity and meaning of work?; 5) Which challenges did the COVID-19 pandemic reveal for the identity and meaning of work in these women?

Guiding by these questions, the objective was to assess whether there would be any change in the work identity in terms of meaning (personal experience in another country) and meanings (socialization process for the work in Brazil and in the US). When considering that the immigrant’s wife could or could not enter the North American job market, the assumption was that this new socialization to work could make them review the meanings and meanings of their work in Brazil.

Thus, this study analyzed the narratives about the work identity and meaning of the work of women who interrupt their careers to accompany their husbands who immigrate to work in another country. Moreover, it compared narratives about the work identity of Brazilian immigrant women who were working in the US with those who were not; it characterized the meanings of the work of Brazilian immigrant women performed paid and non-paid work in the US; and it identified whether the time of residence in the US, the COVID-19 pandemic and the working status had an impact on the work identity and meaning of work of these immigrant women.

It is hoped that this study adds to the literature on female immigrants, helping to understand how moving to another country due to the husbands’ career affects their work identity and meanings attributed to this important sphere of life. In practical terms, it is expected that this study generate inputs to subsidize public policies that offer support to working immigrants. Additionally, the longitudinal design allows apprehending changes in experiences over time, as a result of the process of adaptation of the immigrant to the host country.

Method

Participants

Twelve Brazilian women participated in this research, married to Brazilian immigrants who moved to the state of Michigan (USA) for professional reasons, voluntarily and permanently. Three variables to be detailed later characterized the sample for the purposes of comparative analysis: time of residence in the US, employment status (paid versus non-paid work), before and after the onset of the pandemic.

Qualitative methods scholars vary in defining the ideal number of interviews, which redirects the focus to what each study seeks in terms of the diversity of the symbolic universe of the studied object (Baker & Edwards, 2012). The number was determined by considering two variables: time in the USA (three distinct phases) and paid work (yes or no). It was expected to reach the saturation criterion more easily with this number (Baker & Edwards, 2012; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). The two variables chosen represent an effort to demarcate the manifestation variability of the phenomenon in the context under investigation.

These criteria were aligned with the biographical approach for conducting interviews, which privileges the centrality of individual experiences for the construction of meanings, which justifies the reduced number of representative protagonists (Valsiner, 2012). All participants were Brazilian, living in the US with documented immigration status and, in Brazil, worked in solid higher-level professional careers, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

Labor Insertion |

Participants |

Age |

Length living in the USA |

Field of work in Brazil |

City/State |

Ethnics |

Religion |

English fluency |

Not work |

Marina |

37 |

9 mo |

Veterinay Medicine |

Santos/SP |

White |

No religion |

Intermediary |

Cecília |

42 |

9 mo |

Medicine |

Recife/PE |

White |

Catholic |

Intermediary |

|

Katiusha |

46 |

2 yr 10 mo |

Nursing |

Porto Alegre/RS |

White |

Spiritualist |

Basic |

|

Elisangela |

40 |

3 yr |

Law |

Salvador/BA |

Brown |

Spiritualist |

Intermediary |

|

Diana |

32 |

5 yr |

Education / Supplies |

São Paulo/SP |

White |

No religion |

Fluent |

|

Wanderleia |

39 |

10 yr |

Sales / Tourism |

Porto de Galinhas/PE |

Parda |

Catholic |

Fluent |

|

Work |

Dandara |

34 |

8 mo |

Engineering |

Porto Alegre/RS |

White |

No religion |

Fluent |

Laura |

41 |

8 mo |

Dance |

Barbacena/MG |

White |

Spiritualist |

Basic |

|

Bianca |

48 |

2 yr 6 mo |

Secretariat |

Salvador/BA |

Brown |

Gospel |

Fluent |

|

Melina |

39 |

2 yr 4 mo |

Education |

Sorocaba/SP |

White |

Spiritualist |

Intermediary |

|

Julia |

45 |

5 yr |

Human Resources |

Porto Alegre/RS |

White |

Spiritualist |

Intermediary |

|

Camila |

50 |

10 yr |

Secretariat |

Tatuí/SP |

White |

No religion |

Fluent |

One of the reasons for choosing highly educated women was due to the growing number of immigrants with this profile in the US (Ghatak & Ferraro, 2021). Another reason was the difficulty of accessing middle-level working immigrants. Many end up living in the country without regular immigration status, as they move on their own and cannot get financial support to to regularize their immigration status. Therefore, they are not “accounted for” in the country’s official records, which shows the immense difficulty of arriving at the exact number of immigrants without regular immigration status (Jacobsen & Levin, 2000). In addition, many Brazilian immigrants with high school education who are in the US did not have a consolidated career in Brazil or were even unemployed (Jacobsen & Levin, 2000).

Sample Selection Procedures

Three distinct periods of residence in the country were defined for recruiting participants: up to two years, between two and five years and between five and ten years. Four women belonged to each group, such that two of them were currently on paid work, and two were not. There was an attempt to cover different cycles of permanence in the country, as a way of considering whether the time factor would help to understand the construction, reconstruction or abandonment of identity and meaning of work. In addition, the time for issuing the Green Card (permanent stay visa in the US) is generally two years, which justifies the choice of the first time frame to be up to two years.

In order to meet the second selection criterion of the participants, six women who had paid jobs and six who were only working at home were interviewed. The objective was to have a balanced sample that could facilitate the comparison of the narratives of women who were in the labor market with the narratives of those who were not inserted in the labor market. However, the employment status of three participants changed during the field activity: Marina and Diana (fictitious names), who did not work initially, entered the professional market later, while Melina (fictitious name), who worked, lost her job at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Participants were selected using non-probabilistic accessibility criteria (Batista et al., 2018), using the snowball technique. In order to homogenize the cultural repertoire, only Brazilian women were chosen, as the relationship established with work depends on cultural factors (Rosso et al., 2010).

Instrument

The instruments were four interview protocols, one for each moment of the study. The option for interviews was due to the objective of approaching the experiences and opinions of the participants in their own language (Batista et al., 2018).

In the last two interviews, the timeline strategy was used with figures, texts, response excerpts or other elements. It is important to point out that interviews 3 and 4 were personalized for each participant, considering the answers in the two first interviews, despite the general structure being similar. Basically, two strategies were used in the timeline. In the first, the central responses of each participant were resumed, seeking to identify whether they were maintained. In other situations, figures were brought to illustrate previous responses and stimulate responses about the current relationship with work.

The first protocol was accompanied by a registration form that contained questions regarding the characterization of the participants (e.g., age, marriage’s length, reason for migration, if the participant has kids, original country and arrived date in the USA). Interviews were inspired by the biographical approach, used both to build accounts of women’s life trajectories – focusing on their personal experiences and narratives – and to explore in detail the sociocultural contexts experienced before and after immigration.

Data Collection Procedures

A pilot interview was carried out to then proceed with the necessary adjustments related to the quality and understanding of the questions. All interviews were conducted in Portuguese, with an average duration of one hour. In the first stage, participants signed the consent form, which contained the details of compliance with research ethics, including the need to record the interviews.

With an average interval of seven months, the interviews took place in four moments: March 2019 (M.1); September 2019 (M.2); May 2020 (M.3) and November 2020 (M.4). There were four interviews with each participant, totaling 48 interviews. Initially, three interviews were planned with each participant. However, with the COVID-19 pandemic, which coincided with M.3, it was decided to include one more interview (M.4), balancing two interviews in the pre-pandemic, and two during the pandemic.

The literature recommendation on longitudinal studies is that the choice of data collection interval depends on the variables and contexts studied (Taris & Kompier, 2015). Being the interval smaller, chances are that the independent variable will not have enough time to affect the dependent variable. On the other hand, if the interval between the occurrence of the cause and its potential consequence is too long, the effect of exposure to the explanatory variable may dissapear. The choice of this data collection interval considered that the studied phenomenon is sensitive to the time factor (Baker & Edwards, 2012), especially among women who were not working, since they could enter get a paid job between one interview and another.

Data Analysis Procedures

Four corpus were structured, one for each stage or moment of collection, each with 12 interviews. For the final analysis, a single corpus was created with the 48 interviews. This material was processed through lexical analysis, aided by the Iramuteq software (Interface de R pour les Analyses Multidimensionnelles de Textes et de Questionnaires; Ratinaud, 2009). In addition to being free, the program offers different options for data processing based on textual statistics or lexicometry (Sousa et al., 2020), and is widely used in qualitative studies, especially with interviews (Sousa et al., 2020).

Descending Hierarchical Classification (CHD) was accomplished. This procedure results in a classification that takes advantage of at least 70% of the corpus text segments of the corpus (Camargo & Justo, 2013). The lexical classes can evidence the under or overrepresentation of lexical forms and categorical variables associated with the text segments of the corpus, according to indicators based on chi-square tests.

In each class, differences will be mentioned (overrepresentation or underrepresentation) in relation to the study’s key variables: a) constructs identity; meaning of work; b) before or during the pandemic (M1 and M2 vs. M3 and M4); c) who is short, medium or long term in the US, and d) those with paid and non-paid jobs.

Results

Descending Hierarchical Classification (CHD)

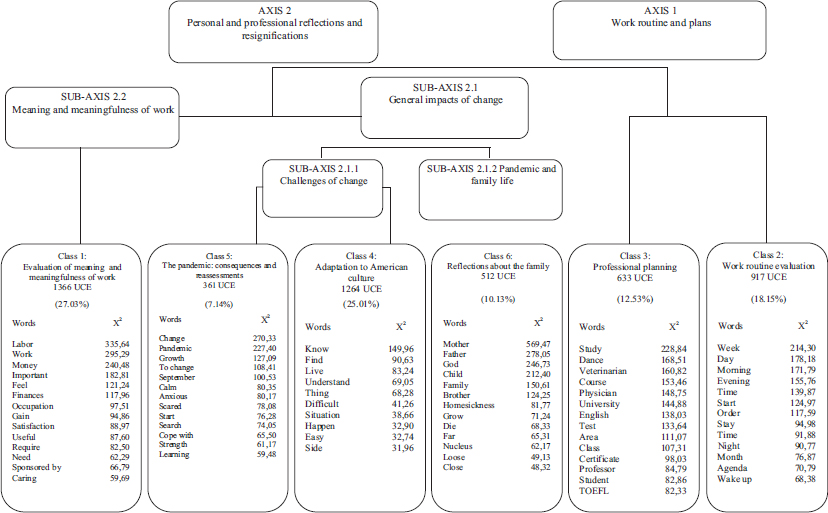

Of the 5185 text segments in the corpus, 5053 were distributed in the classification, representing 97.45% of the total. Figure 1 presents the corpus dendrogram divided into two axes and six lexical classes, including the 10 words with the highest χ² (≥ 3.84; < 0.05) (Camargo & Justo, 2013). The classes were named based on the reading of most characteristic text segments and the identification of the main themes associated with the vocabulary of the class.

Figure 1. Dendrogram of the corpus general synthesis of the interviews

The “Work routine and plans” axis was composed of classes 2 “Work routine evaluation” (18.15%) and 3 “Professional planning” (12.53%). The axis “Personal and professional reflections and resignifications” was composed of classes 1 “Evaluation of meaning and meaningfulness of work” (27.03%), 4 “Adaptation to American culture” (25.01%), 6 “Reflections about the family” (10.13%) and 5 “The pandemic: consequences and reassessments” (7.14%).

The layout of the axes reveals that despite the identification of six classes, two of them concentrate about half of the text segments: classes 1 “Evaluation of meaning and meaningfulness of work” and 4 “Adaptation to American culture”, with, respectively, 27.03% and 25.01% of the corpus. This means that a significant amount of textual segments related to how the work was seen regarding the meaningfulness and meaning elements (class 1) and what were the challenges encountered in the process of leaving Brazil and arriving in the USA (class 4). In turn, the lower dispersion of data among the other classes may indicate narratives focused on specific subjects, or even generating less impact on the lives of these women, such as the work routine, activities related to the family and the pandemic.

Axis 1: “Work Routine and Plans”

Each axis of the Dendrogram, mentioned in Figure 1, will be presented. Composed of classes 2 “Work routine evaluation” and 3 “Professional planning”, this axis brings together narratives about how the participants evaluated the routine and plans in relation to work. Observing the characteristics of vocabulary use, it appears that both bring together narratives that address the theme of work. One focuses more on future professional plans, and the other on the work routine.

Class 3: “Professional Planning”

It evidences plans about the work trajectory that these women wanted for the present and the future. The text segments from the first two moments are overrepresented in M.1 (χ² = 39.285) and M.2 (χ² = 14.121), as well as those that were produced in stages of the interview dedicated to the identity construct (χ² = 53.340 ).

There were also concerns about the validation of the diploma: “revalidating would be a possibility because I like to study and to be a doctor, you need to like studying” (Cecília, personal interview, March 2019). And there was a plan linked to improving fluency in English: “another project would be to work in the translation area at the University of Michigan. I would be developing my English” (Katiusha, personal interview, September 2019) (the underscores refer to words with significant chi-square and class representativeness). Other narratives are more connected to professional life in Brazil or professional replanning, based on the new reality found in the USA: “I want to go back to studying and dancing here in the USA” (Laura, personal interview, September 2019).

Class 2: “Work Routine Evaluation”

This class includes the participants’ routine, especially their work, in Brazil and in the USA. Overrepresented in this class are the narratives coming from: a) the third moment (M.3 (χ² = 14.654); b) working women (χ² = 9.029) and c) focusing on identity (χ² = 26.334).

Some narratives deal with the routine they had in Brazil or the beginning of their lives in the USA, such as: “I would go to the library in Ann Arbor and spend about 6 hours a day there. In the afternoon, I would come back” (Camila). Other narratives contextualize how these women needed to adapt their working lives to the new American routine. There are aspects that involve the planning phase or the new working environment in the USA: “on my first day at the manufacture, people started to leave at 3 pm. Too early. And another thing is that people don’t have a lunch break” (Dandara, personal interview, May 2020).

It can also be noticed how some women changed their routine depending on the new professional plans they were developing or the need to rebuild their professional lives: “then today I work in the morning, and I manage to organize myself to study a few more days a week at home, and I have a better quality of life” (Julia, personal interview, May 2020).

Finally, we added how the pandemic changed the participants’ routine, based on the following narratives: a) “my routine changed a lot with the pandemic. I started to wake up in the morning, go to the computer and spend hours on the computer. Then I read all afternoon” (Marina); b) “in the last 3 days, I go downstairs and work in the kitchen until lunchtime. And my daughter stays by my side playing” (Diana, personal interview, May 2020).

Axis 2: “Personal and Professional Reflections and Resignifications”

Composed of classes 1 “Evaluation of meaning and meaningfulness of work”, 4 “Adaptation to American culture”, 6 “Reflections about the family” and 5 “The pandemic: consequences and reassessments”, the axis brings together narratives arising from reflections on life personal and professional, including the potential effects of the pandemic on this process.

Classes 4, 5 and 6 are linked to the sub-axis “General impacts of change” and separate them from class 1 in the sub-axis “Meaning and meaningfulness of work”. Classes 4, 5 and 6 are thematically similar in that they focus on the reflections caused by changing situations, such as adapting to the US and evaluating aspects of life that the pandemic has provided: immediate reactions to physical distancing, research of aspects such as family value and individual strategies to deal with changes.

Class 1 brings together narratives about the meaning and significance of work, both before and after the pandemic. In turn, classes 4, 5 and 6 were divided into two new subaxes. One brings together classes 4 and 5, in the sub-axis “Challenges of changing”, which deals with reflections caused by the pandemic and about how the process of moving to the US was, including the challenges and growth. The other sub-axis, named “Pandemic and family life”, separates class 6 from the others, highlighting narratives specifically linked to the reassessment of the importance of the family.

Class 1: “Evaluation of meaning and meaningfulness of work”

It deals with reflections on the constructs meaningfulness and meaning of work. The overrepresented text segments in this class: a) are related to the meaning of work (χ² = 49.222) and meaningfulness of work (χ² = 29.486); b) were produced by working women with paid jobs (χ² = 5.255); and c) related to moments before the pandemic M.1 (χ² = 10.836) and M.2 (χ² = 106.416).

The first reflection is about the change in the meaning of work in relation to money:

I work to be independent, have my money and feel active and useful. I think the meaning has changed a little for me because I used to work more for the money. I didn’t have the option of not working, you know? Today, my husband is the main breadwinner. I no longer need to work for money. So, today, the meaning of work is to have your financial gain, money enough to support yourself and your family, but the most important thing is to be happy with your work. (Bianca, personal interview, March 2019, M.1)

Along the same lines, the meaning of work became more linked to a meaningfulness of usefulness and self-esteem:

It’s so nice to take my husband out to dinner or to buy a present. For him, today, I’m not making any effort, because I don’t work. It’s not the same when you don’t work, it doesn’t have that same pleasure of knowing that you work, that you have that responsibility. (Laura, personal interview, September 2019, M.2)

In this class, there are also narratives about new meanings of work attributed to work: a)

What was passed on to me is that work is very important, that it is my means of independence and security. But today it changed. Today the meaning of work is to feel fulfilled, feeling good about myself, not for others, for me. (Camila, personal interview, May 2020, M.3)

b)

What I was taught is that work was a source of independence, of earning money, that being free to do what you want with your life and a source of self-fulfillment. Here the meaning is more connected to pleasure. (Dandara, personal interview, March 2019, M.1)

Class 4 “Adaptation to American Culture”

This class brings together narratives related to the process of general adaptation of women to the US, especially the difficulties. The overrepresented text segments in this class were related to identity (χ² = 26,299). The following quote illustrates the challenges associated with the personal difficulty of linking to the US due to a stronger link with Brazil: “I have been very attached to Brazil, now in the pandemic, because it´s difficult to break from time to time. I think I’ve been living here for a short time” (Laura, personal interview, May 2020, M.3).

There is also a narrative marked by language challenges: “I think that this culture thing we learn to deal with, but I still feel a bit silly. It’s hard not to be understood with my English. In the pandemic, I think that feeling got worse” (Melina, personal interview, November 2020, M.4). Other adaptation difficulties are related to the need to reconcile many roles in the US, such as taking care of the family and children:

I think that motherhood and moving to the US made it difficult for me to adapt because it is difficult living with a child, without help, like in Brazil. I don’t feel pleasure doing so much at home; I would like help. I came here, but I didn’t know that my life would be like this. (Katiusha, personal interview, September 2019, M.2)

Or else: “I feel very lonely having to do so many things. But, what am I going to do? Go away and leave my family here? It’s hard” (Camila, personal interview, March 2019, M.1). There is also:

Here I know that it is necessary to adapt professional life to taking care of the house and the children. I don’t think I’m going to work like I used to. I think I want a quieter job so I can have time to take care of the family. (Melina, personal interview, May 2020, M.3)

And finally:

You come, but when you live, the reality is different. I know I’m going to start from the bottom, I think changing areas. I know I came because of my husband’s work, but it’s that thing, I want to evolve too. (Wanderleia, personal interview, November 2020, M.4)

But, at the same time, it is possible to perceive a need to return to the job market: “it is difficult just to take care of a child. I knew I didn’t want just this forever. Today I understand. In the future, I want to work” (Katiusha, personal interview, March 2019, M.1).

Other elements of the change process are more closely linked to positive consequences. One of them is the acquired practicality or learning to live far from the family that stayed in Brazil:

So I think that for a while when I moved here, this change brought me a lot of suffering because I had to understand and live without my family and my profession, but today I think I learned to live with the situation. (Melina, personal interview, September 2019, M.2)

Class 5: “The Pandemic: Consequences and Reassessments”

This class includes narratives related to the impacts generated by the pandemic on personal and professional life, from the perspective of difficulties and also lessons learned from the pandemic. It is an attempt to analyze and make of reality, besides experiencing how to deal with the situation in a more positive way. The overrepresented text segments in this class: a) were produced in the two moments after the start of the pandemic, M.3 (χ² = 5.047) and M.4 (χ² = 41.546); and b) are related to work identity (χ² = 12.465).

The following narrative excerpt illustrates the uncertainties arising from the pandemic: “Today, the pandemic brought this change: not controlling the future”. (Elisangela, personal interview, May 2020, M.3). Other consequences of the pandemic were personal changes. A personal change was linked to personality characteristics or a more assertive way of dealing with the future: “then there was a stir again, chaos came in again, doubts came in. So there will be changes around and I still don’t know what changes they will be, but changes are coming” (Bianca, personal interview, November 2020, M.4).

There are also narratives centered on work, but more linked to the change in the importance of work, stimulated by the pandemic: “within this concept of moving to another country, my priority is no longer work, but the pandemic gave a boost to this thinking” (Camila, personal interview, May 2020, M.3).

Class 6: “Reflections about the Family”

This last class portrays how these women revisited the importance of family after the pandemic, be it the family that resides with them in the USA, or the family that was left behind in Brazil. The overrepresented text segments in this class: a) were produced in the two moments after the start of the pandemic, M.3 (χ² = 13.833) and M.4 (χ² = 3.429) and b) are related to the construct work identity (χ² = 12,222).

The narratives find support in the premise that some reflections were being made with the move to the US, but intensified with the pandemic. A first reflection comes from the importance of the family: “today the issue of the core family is more important now because of the pandemic. I think the pandemic affected us a lot because I think it’s important to value the family we have close to us” (Katiusha, personal interview, May 2020, M.3).

Finally, another reflection stems from the need to live socially with other people in the US, in addition to family members:

Here everyone lives their own life and I think Brazilians care more and just as I have children now, I don’t think I want my children to grow up in a cold way, thinking that their life is just father, mother and brother. (Elisângela, personal interview, November 2020, M.4)

The narratives also reveal the absence of the family left behind in Brazil: “because in Brazil, our nucleus would be our husband, our son, our family, mother, father. It’s a much bigger thing besides friends. Here, you don’t have this big nucleus, right? I really miss everything there in Brazil” (Diana, personal interview, May 2020, M.3).

Discussion

Analyzing the results of Class 1 “Evaluation of meaning and meaningfulness of work”, it was noticed that the text segments of working women are overrepresented in this class (χ² = 5.255). Considering that the diversity of meaning and meaningfulness of work permeates the way the worker understands and attributes value to his work (Rossit et al., 2018), participants with paid jobs addressed these themes more, possibly because their work context facilitates the assessment of the purpose of work, to the detriment of those who are dedicated only to work at home.

Considering that the meaningfulness and meaning of work are influenced by the context in which it is produced (Rosso et al., 2010), for these women these constructs underwent changes with immigration. To the detriment of the financial value that the work had, the new meaningfulness and meaning became fulfillment, pleasure, usefulness, self-esteem, happiness, going beyond financial gain (Bilgic & Yilmaz, 2013).

Possibly, in a context in which the economic decision to work becomes less urgent, the workforce is minimized. The husband’s salary, combined with a less unfavorable cost of living, may be elements that allow greater flexibility in valuing the monetary aspect. Data from the Economic Policy Institute (2021) indicate that Michigan state, where all of the participants lived, is the sixth highest-paying state in the US.

While the results of Class 1 “Evaluation of meaning and meaningfulness of work” revealed the prevalence of restructuring of meanings among women who were in the US labor market, data from Class 3 “Professional Planning” and Class 4 “Adaptation to American Culture” did not indicate overrepresentation of narratives based on employment status. In other words, the elaboration of professional plans and the search for adjustment strategies to the new country occurred whether these wives worked or not. Therefore, regardless of the employment situation of these wives who migrate to accompany their husbands, moving to a new country suggests having had a general shared impact on the challenges of adapting to the new culture, which is starting to require the construction of new professional plans that are not always related to the professional lives they had in Brazil.

Still in classes 3 and 4, overrepresentation was found only in the text segments about work identity (Class 3 [χ² = 53.340]; Class 4 [χ² = 26,299]), suggesting that this identity can be impacted when a person moves to another country, as they need to prepare or remake professional plans in order to adapt to the new context in which they are inserted. The elements of these classes also suggest that none of the participants stopped considering paid work as an important activity in their lives, constituting part of their self-concept (Byron & Crafford, 2012).

Wives with paid jobs repositioned the centrality of work and modified the work identity. On the other hand, wives who were working at home, in general, temporarily replaced the idea of work linked only to the formal job market. Due to the demands and challenges of American culture, they considered taking care of children and being at home as a momentary job, but without ceasing to wish to return to the job market. With the mass entry of women into the labor market, especially married women with dependent children, it is increasingly common for families to be maintained by both spouses (Castro, 2021).

In addition, the social and cultural devaluation of housework encourages the perception that household activities are not “work” (Federici, 2019) when these women change their labor status from Brazil (paid work combined with domestic work) to the US (only domestic work). Domestic work, therefore, continues to be seen as a weakening factor in the work identity. Caring for and monitoring the child and the house, taking a course and learning the language competed with a work identity that sought to be achieved by exercising professional roles outside the home. In a study regarding career and relocation decisions among 21 heterosexual, young adult couples, Paul Wong (2017) evidenced how gendered negotiation trajectories affect work–family decisions which both contest and reproduce gendered outcomes. On the “change desires” pathway, specifically, women perform emotional work to relinquish desires for career and justify a neotraditional division of labor, which seems to also be the case in the present study.

On the other hand, domestic work was incorporated into women’s customs as a gift: work done out of love (Federici, 2019). Despite the option of building a work identity with activities outside the home, many women experience social pressure to deal with the traditional roles imposed on them of taking care of the house and children (Bentley et al., 2019). It was visible in the narratives of women who participated in this study. They abandoned their work bonds in Brazil and faced a lack of social support to invest in their careers in the new country, reliving providers’ and caregivers’ social roles, which brought challenges to building new professional careers.

The representations regarding the differences between masculine and feminine are derived from social determinants to which women are subjected, which makes them feel guilty when they do not give up their professional life for some family need (Aizawa & de Azevedo, 2022). This may explain why, in Brazilian culture, it is predictable that women will give up paid work and career projects to accompany their husband to another country, even if this act involves a lot of effort. There are workplaces that still privilege men over women, and cultural schemas that link family to femininity make it challenging for couples to equally share responsibilities (Kramer et al., 2015).

As an alternative to such reality, couples may reconcile their desires with gendered structures and cultural contexts as they bargain over work–family arrangements by performing emotional labor (Wong, 2017). Couples can do emotion work to maintain egalitarian desires by resisting the prescriptions of the gender, work devotion, and family devotion schemas. They can perform practical work by asking for flexible work arrangements, evenly contributing to domestic responsibilities, or sustaining long-distance commuter relationships that accommodate individuals’ pursuits while maintaining a sense of family (van der Klis & Mulder, 2008). However, only a few participants reported such strategies from their male spouses, which evidences the gendered power dynamics at play.

In many heterosexual relationships, the man is in the power position or even earns more than his wife, which may also have weighed on the decision of some participants to give up their careers. In most cases, these women may still be financially dependent on their husbands. There is, then, a bond of moral commitment to unpaid domestic tasks, a situation that can cause suffering (Federici, 2019). Adding to this fact is the situation of women who, when starting their lives over in a new country, are more likely to engage in low-paid activities, which makes them give up entering the labor market. That is, many women may feel in a dead-end situation. Another relevant contextual element is the fact that in the US, families most often do not have the help of nannies or maids (Bertoldo, 2018). For this reason, it is common for one of the family members, in most cases the woman, to start working at home to take care of the household chores and the children, even if temporarily.

Furthermore, in the USA, American mothers are entitled to time off from work for the first 12 weeks of the baby’s life, albeit without pay (Becker & Piccinini, 2019). Some mothers, because they think this is not time enough, choose to take care of their children exclusively, given the high cost of daycare, being free education only available from the age of five (Azzoni & Almeida, 2021).

The text segments of Class 5 “The Pandemic: Consequences and Reassessments” point out that the pandemic generated the need to postpone or remake professional plans. This does not mean that, during the pandemic, plans ceased to exist. Working life took on another meaning for these women, which meant that professional plans were temporarily interrupted or suspended. The pandemic also brought unemployment, which undeniably can have repercussions on changing plans and ways of working (Costa, 2020). Therefore, it is assumed that there were changes in the work identity. Data also support the hypothesis of a temporary interruption of the strength of the work identity, as a result of the pandemic, due to the increased demand for work at home and the repositioning of values, prioritizing the family to the detriment of work.

Finally, regarding Class 6, “Reflections about the Family”, previous research indicates that women who only moved because their husband wanted to were the least satisfied, with negative feelings often repressed in interaction to support the husband or to rationalize the move in terms of what was in the best interests of the family (Hiller & McCaig, 2007), which was also identified in this research. As indicated in some quotes, women who missed family and friends back home faced the social costs of separation with expressions of emotional ambivalence about the move.

Conclusions

Overall, the goals set for this research were met and the research questions were answered, being summarized as follows: a) in general, the migrating wives rebuilt their work identity as they needed to adapt to a new country to the pandemic consequences, restructuring professional plans and routines; b) differences were noticed between the two participating groups, as those with paid jobs sought to re-signify work with the intention of adapting to the work context they found. Those on non-paid jobs and only working at home temporarily completed this identity through housework and child care, however, with the future intention of returning to the paid job market; c) the work identity was based on new meaningfulness and meaning of work as a search for happiness, purpose, pleasure, occupation of time, etc., predominantly among women who worked outside the home; d) the main variable affected by the pandemic was work identity; and e) unlike labor status and the pandemic, the variable length of residence in the US did not prove to be central in the complex dynamics of construction of meaning and identity in the new country.

In relation to the three variables of the study, the labor status (women with paid jobs) interfered more in changing the meaning of work, while the pandemic greatly impacted the work identity. The time of residence did not present relevant effects, such that possibly the feeling of strangeness in the new country caused by the need to uproot is something that impacts the immigrant for the long term. Even incorporating the new social rules, she has the feeling of remaining a foreigner in another country, even if she becomes a citizen.

Overall, this also study contributes to the knowledge on gender, work, and family by showing how the process of immigration for career purposes remains gendered, even with attitudinal shifts towards egalitarianism among a few couples (Pedulla & Thébaud, 2015). Unfortunately, findings corroborate research that shows women disproportionately shoulder the burden of geographic relocation, with them assuming the responsibility for achieving work–family balance (Bielby & Bielby, 1992; Mincer, 1978; Shihadeh, 1991). Cultural narratives of “superwomen” who master work–family balance may also contribute to this gendered division of responsibility (Wong, 2017).

This study made progress in gaps observed in previous research as it deepened the process of adapting to a new country and its influence on the construction of the work identity, also capturing the effects of COVID-19 on these relationships. Regarding methodological contributions, it was used a longitudinal design that allowed gathering information at four different times, differing from studies that capture data at a specific time (Bendassolli & Gondim, 2014).

The limitations involve the participants, which belonged to hetero-affective families. New studies could consider families with different constitutions to understand the diversity in the disposition of gender roles. Furthermore, all 12 women were higher educated and belonged to the middle or upper middle class in Brazil, which makes their adaptation process different from that of an immigrant who has only a high school education. Studies that differentiate immigrants from different educational levels could bring new information. Interviewees resided in the same state, Michigan, which imposes caution on the generalization of conclusions about repositioning the identity and meaning of the work of a Brazilian immigrant living in another USA state. It is also important to emphasize that the women in the research belong only to the white or brown race.

Another aspect to consider is that only the interview was used as a field analysis technique. Other studies could include complementary techniques (e.g., observation, focus groups, questionnaires, etc.) in order to obtain additional information that could help in the interpretation of the data. As for the interview analysis technique, the use of Iramuteq alone can be considered a limiting factor, as other techniques such as content analysis or thematic analysis would point to additional perspectives.

Future studies should better investigate the influence of different previous relationships with work, as well as the development of immigration supportive policies, such as, offering language courses, key information on processes of revalidation of diploma and availability of job openings. Organizations could also adopt policies that help in the process of adaptation and socialization of immigrant workers, offering a more receptive environment towards diversity. Another suggestion would be the development of an intervention program aimed at career guidance for immigrants.

References

Aizawa, Juliana T. R., & de Azevedo, Heloisa M. (2022). Maternidade e a evasão laboral: Alguns aspectos da licença maternidade, salário maternidade e auxílio creche [Maternity and work evasion: some aspects of maternity leave, maternity pay and daycare allowance]. Perspectivas em Diálogo: Revista de Educação e Sociedade, 9(19), 21-43. https://doi.org/10.55028/pdres.v9i19.13038

Américo, Ekaterina V. (2017). The concept of border in yuri lotman’s semiotics. Bakhtiniana, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1590/2176-457326361

Azzoni, Carlos R., & Almeida, Alexandre N. (2021). Mudanças nas estruturas de consumo e custo de vida comparativo nas Regiões Metropolitanas: 1996-2020 [Changes in consumption structures and comparative cost of living in Metropolitan Regions: 1996-2020]. Estudos Econômicos, 51(3), 529-563. https://doi.org/10.1590/0101-41615134caaa

Baker, Sarah E., & Edwards, Rosalind. (2012). How many qualitative interviews is enough? National Center for Research Methods. https://eprints.ncrm.ac.uk/2273/

Bastos, Cristiana. (2020). Febre a bordo: migrantes, epidemias, quarentenas [Fever on board: migrants, epidemics, quarantines]. Horizontes Antropológicos, 26(57), 27-55. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0104-71832020000200002

Batista, Eraldo C.; Matos, Luis A. L., & Nascimento, Alessandra B. (2018). A entrevista como técnica de investigação na pesquisa qualitativa [The interview as an investigation technique in qualitative research]. Revista Interdisciplinar Científica Aplicada, 11(3), 23-38. https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=361453972028

Becker, Scheila M. S., & Piccinini, Cesar A. (2019). Impacto da creche para a interação mãe-criança e para o desenvolvimento infantil [Impact of day care on mother-child interaction and child development]. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 35, 35-42. https://doi.org/10.1590/0102.3772e3532

Bendassolli, Pedro F., & Gondim, Sônia M. G. (2014). Significados, sentidos e função psicológica do trabalho: Discutindo essa tríade conceitual e seus desafios metodológicos [Meanings, senses and psychological function of work: Discussing this conceptual triad and its methodological challenges]. Avances en Psicología Latino-americana, 32(1), 131-147. https://doi.org/10.12804/apl32.1.2014.09

Bentley, Sarah; Peters, Kim; Haslam, Sam, & Greenaway, Katharine. (2019). Construction at Work: Multiple Identities Scaffold Professional Identity Development in Academia. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 628-640. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00628

Bertoldo, Jaqueline. (2018). Migração com rosto feminino: Múltiplas vulnerabilidades, trabalho doméstico e desafios de políticas e direitos [Migration with a female face: Multiple vulnerabilities, domestic work and policy and rights challenges]. Revista Katálysis, 21(2), 313-323. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-02592018v21n2p313

Bertrand, Marianne; Kamenica, Emir, & Pan, Jessica. (2015). Gender Identity and Relative Income Within Households. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(2), 571–614. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26372609

Bielby, Willian T., & Bielby, Denise D. (1992). I will follow him: Family ties, gender-role beliefs, and reluctance to relocate for a better job. American Journal of Sociology, 97(5), 1241–1267. https://doi.org/10.1086/229901

Bilgiç, Reyhan, & Yılmaz, Nilgun. (2013). The correlates of psychological health among the Turkish unemployed: Psychological burden of financial help during unemployment. International Journal of Psychology, 48(5), 1000–1008. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.717702

Boyd, Monica. (1989). Family and personal networks in international migration: Recent developments and new agendas. The International Migration Review, 23(3), 638–670. https://doi.org/10.2307/2546433

Byron, Adams, & Crafford, Anne. (2012). Identity at work: Exploring strategies for identity work. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology, 38(1), 120-131. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajip.v38i1.904

Camargo, Brigido V., & Justo, Ana M. (2013). Iramuteq: um software gratuito para análise de dados textuais [Iramuteq: free software for textual data analysis]. Temas em Psicologia, 21(2), 513-518. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2013.2-16

Castro, Marcela M. (2021). Covid-19 e trabalho de mulheres-mães-pesquisadoras: impasses em “terra estrangeira” [Covid-19 and the work of women-mothers-researchers: impasses in a “foreign land”]. Linhas Críticas, 27. https://doi.org/10.26512/lc27202136370

Cazarotto, Rosmari T., & Sindelar, Fernanda C. W. (2020). A dinâmica da imigração laboral internacional contemporânea: o caso do Vale do Taquari/RS no período de 2010-2018 [The dynamics of contemporary international labor immigration: the case of Vale do Taquari/RS in the period 2010-2018]. Geosul, 35(75). https://doi.org/10.5007/1982-5153.2020v35n75p257

Challiol, Hélène, & Mignonac, Karim. (2005). Relocation decision-making and couple relationships: A quantitative and qualitative study of dual-earner couples. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(3), 247–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.311

Costa, Simone S. (2020). Pandemia e desemprego no Brasil [Pandemic and unemployment in Brazil]. Revista de Administração Pública, 54(4), 969-978. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-761220200170

Economic Policy Institute. (2021). Identifying the policy levers generating wage suppression and wage inequality. https://www.epi.org/unequalpower/publications/wage-suppression-inequality/

Federici, Silvia. (2019). Calibã e a Bruxa [Caliban and the Witch]. Editora Elefante.

Ghatak, Saran, & Ferraro, Vincent. (2021). Immigration control and the white working class: explaining state-level laws in the US, 2005–2017. Sociological Spectrum, 41(6), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2021.2004272

Gherlone, Laura. (2019). A escrita feminina entre a fronteira e o não lugar: Discursos femininos em ascensão na Literatura Italiana de Migração [Feminine writing between the border and the non-place: Feminine discourses on the rise in Italian Migration Literature]. Revista de Estudos do Discurso, 14(2), 6-24. https://doi.org/10.1590/2176-457339335

Gjerde, Susann, & Alvesson, Mats. (2020). Sandwiched: Exploring role and identity of middle managers in the genuine middle. Human Relations, 73(1), 124–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718823243

Glaser, Barney, & Strauss, Anselm. (1967). The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Sociology Press.

Han, Shin K., & Moen, Phyllis. (1999). Work and family over time: A life course approach. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 562(1), 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271629956200107

Hiller, Harry H, & McCaig, Kendall S. (2007). Reassessing the role of partnered women in migration decision-making and migration outcome. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 24(3), 457-472. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507077233

Houstoun, Marion F.; Kramer, Roger G., & Barrett, Joan M. (1984). Female predominance in immigration to the united states since 1930: A first look. International Migration Review, 18(4), 908–963. https://doi.org/10.1177/019791838401800403

International Organization for Migration. (2021). World Migration Report 2021. https://publications.iom.int/system/files/pdf/wmr_2021.pdf

Jacobsen, Joyce P., & Levin, Laurence M. (2000). The effects of internal migration on the relative economic status of women and men. Journal of Socio‐Economics, 29(3), 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1053-5357(00)00075-5

Jinnah, Zaheera. (2017). Cultural causations and expressions of distress: A case study of buufis amongst somalis in johannesburg. Urban Forum, 28(1), 111-123. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-016-9283-y&

Kramer, Karen Z.; Kelly, Erin L., & McCulloch, Jan B. (2015). Stay-at-home fathers: Definition and characteristics based on 34 years of CPS data. Journal of Family Issues, 36(12), 1651–1673. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X13502479

Massey, Douglas S.; Arango, Joaquín; Hugo, Graeme; Kouaouci, Ali; Pellegrino, Adela, & Taylor, J. Edward. (1993). Theories of international migration: A review and appraisal. Population and Development Review, 19(3), 431–466. https://doi.org/10.2307/2938462

Mincer, Jacob. (1978). Family Migration Decisions. Journal of Political Economy, 86(5), 749–773. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1828408

Morokvasic, Mirjana. (1984). Birds of passage are also women. International Migration Review, 77(1), 7-25. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2546066

Pedulla, David S, & Thébaud, Sarah. (2015). Can we finish the revolution? gender, work-family ideals, and institutional constraint. American Sociological Review, 80(1), 116–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414564008

Ratinaud, Pian. (2009). IRaMuTeQ: Interface de R pour les analyses multidimensionnelles de textes et de questionnaires — 0.7 alpha 2 [RaMuTeQ: R interface for multidimensional analyzes of texts and questionnaires]. https://www.iramuteq.org/

Reeves, Scott. (2016). Ideas for the development of the interprofessional education and practice field: an update. J Interprof Care, 30(4), 405-7. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820.2016.1197735

Reis, Daniela P., & Puente-Palacios, Katia. (2019). Team effectiveness: The predictive role of team identity. RAUSP Management Journal, 54(2), 141-153. https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-07-2018-0046

Rossit, Rosana A. S.; Freitas, Maria A. O.; Batista, Sylvia H. S. S., & Batista, Nildo A. (2018). Construção da identidade profissional na Educação Interprofissional em Saúde: percepção de egressos [Construction of professional identity in Interprofessional Health Education: perception of graduates]. Interface, comunicação, saúde e educação, 32(1), 399-410. https://doi.org/10.1590/1807-57622017.0184

Rosso, Brent; Dekas, Kathryn, & Wrzesniewski, Amy. (2010). On the meaning of work: a theoretical integration and review. Research in Organizational Behavior, 30, 91-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2010.09.001

Rudman, Laurie, & Phelan, Julie. (2008). Backlash effects for disconfirming gender stereotypes in organizations. Research in organizational behavior, 28, 61-79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.riob.2008.04.003

Shihadeh, Edward S. (1991). The prevalence of husband-centered migration: Employment consequences for married mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 53(2), 432–444. https://doi.org/10.2307/352910

Sousa, Yuri S. O.; Gondim, Sônia M. G.; Carias, Iago A.; Batista, Jonatan S., & Machado, Katlyane C. M. (2020). O uso do software Iramuteq na análise de dados de entrevistas [The use of Iramuteq software in the analysis of interview data]. Pesquisas e Práticas Psicossociais [Psychosocial Research and Practices], 15(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1980-220X2017015003353

Taris, Toon W, & Kompier, Michiel A. J. (2015). Cause and effect: Optimizing the designs of longitudinal studies in occupational health psychology. Work & Stress, 28(1), 1–8. https://doi//10.1080/02678373.2014.878494

Ullrich, Jan; Pluut, Helen, & Büttgen, Marion. (2015). Gender differences in the family-relatedness of relocation decisions. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 90, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.06.003

United Nations Organizations. (2021). Report of the Secretary-General on the Work of the Organization. https://www.un.org/annualreport/2021/files/2021/09/2109745-E-ARWO21-WEB.pdf

Valsiner, Jaan. (2012). Fundamentos da Psicologia Cultural - Mundos da mente, mundos da vida [Fundamentals of Cultural Psychology - Worlds of the mind, worlds of life]. Artmed.

van der Klis, Marjolijn, & Mulder, Clara H. (2008). Beyond the trailing spouse: the commuter partnership as an alternative to family migration. J Hous and the Built Environ, 23, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-007-9096-3

Winkelman, Michael. (1994). Cultural shock and adaptation. Journal of Counseling & Development, 73(2), 121-126. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1994.tb01723.x

Wolfinger, Nicholas; Mason, Mary, & Goulden, Marc. (2009). Stay in the game: Gender, family formation and alternative trajectories in the academic life course. Social Forces, 87(3), 1591–1621. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.0.0182

Wong, Paul T. P. (2017). Meaning-centered approach to research and therapy, second wave positive psychology, and the future of humanistic psychology. The Humanistic Psychologist, 45(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1037/hum0000062

Zvonkovic, Anisa M.; Schmiege, Cynthia J., & Hall, Leslie D. (1994). Influence strategies used when couples make work-family decisions and their importance for marital satisfaction. Family Relations, 43(2), 182-188. https://doi.org/10.2307/585321

Silvana Curvello de Cerqueira Campos

PhD from the Social and Work Psychology Program at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), master from the same program, graduated in Psychology and Specialist in People Management. Currently, she is an analyst at Salvador City Hall, having previously been Training Manager at Empresa Baiana de Águas e Saneamento.

scurvellocampos2019@hotmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2809-4726

Sônia Maria Guedes Gondim

Psychologist and retired Full Professor at the Institute of Psychology at UFBA, with a master’s degree in Social Psychology from Gama Filho University and a doctorate in Psychology from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro.

sggondim@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3482-166X

Ligia Carolina Oliveira-Silva

Professor at the Institute of Psychology and the Postgraduate Program in Psychology at the Federal University of Uberlândia. PhD and Master’s degree from the Postgraduate Program in Social, Work and Organizational Psychology (PSTO) at the University of Brasília (UnB).

ligiacarol1987@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7487-9420

Yuri Sá Oliveira Sousa

Psychologist (2010), Master (2013) and Doctor (2017) in psychology from the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE), with a doctoral internship (2014-2015) at the Laboratoire de Psychologie Sociale at Aix-Marseille Université. He is currently Adjunct Professor III at the Institute of Psychology at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA).

yurisousas@gmail.com

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8713-5543

Formato de citación

Campos, Silvana; Gondim, Sônia; Oliveira-Silva, Ligia, & Sousa, Yuri. (2025). Work Identity, Meaning and Meaningfulness of Work: Brazilian Women Immigrants in the USA. Quaderns de Psicologia, 27(2), e2158. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.2158

Historia editorial

Recibido: 20-04-2024

1ª revisión: 02-07-2024

Aceptado: 15-08-2024

Publicado: 29-08-2025