Quaderns de Psicologia 2025, Vol. 27, Nro. 1, e2107 | ISSN: 0211-3481 |

https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.2107

https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.2107

LGBT Climate Inventory in Corporations for Straight People?

¿Un inventario del clima LGBT en las empresas para personas heterosexuales?

Leon Freude

Universitat Pompeu Fabra

Jordi Bonet-Martí

Universitat de Barcelona

Abstract

Open societies are eager to accommodate sexual and gender diversity at work. The Lesbian, Gay, Bisexuals and Trans Climate Inventory (LGBTCI) is an instrument measuring organizational climate towards sexual and gender diversity, relying on the opinion of LGTB people. We argue that non-LGTB employees also perceive a climate towards sexual and gender diversity, and therefore include them to measure LGBT-friendly climate at work. By means of a Multiple Correspondence Analysis (MCA) we validate this application of the LGBTCI obtaining two factors: first, comprehension of the items linked to sexual and gender diversity; second, positioning with respect to the climate. We contribute to existing research claiming that non-LGBT employees should be incorporated in the measurement of the climate.

Keywords: LGBT; Sexual and Gender Diversity; LGBT Climate Inventory; Work; Inclusion

Resumen

Las sociedades abiertas se caracterizan por su deseo de acoger la diversidad sexual y de género en los lugares de trabajo. En este sentido, el Inventario de Clima para Lesbianas, Gays, Bisexuales y Trans (LGBTCI) es un instrumento que mide el clima organizacional hacia la diversidad sexual y de género, basándose en la opinión de las personas LGTB. En este artículo, argumentamos que los empleados no LGTB también pueden percibir el clima hacia la diversidad sexual y de género y, por lo tanto, los hemos incluido para medir el clima favorable a las personas LGTB en el trabajo. Mediante un Análisis de Correspondencias Múltiples (ACM) hemos validado esta aplicación del LGBTCI obteniendo dos factores: la comprensión de los ítems vinculados a la diversidad sexual y de género, y el posicionamiento respecto al clima. Este artículo supone una contribución a las investigaciones previas que consideraban que los empleados no LGBT no deberían ser incorporados a la medición del clima organizacional en las empresas.

Palavras-chave: LGBT; Diversidad sexual y de género; LGBT Inventario de clima; trabajo; Inclusión

Introduction and background

The aim of this article is to discuss if the LGBT Climate Inventory could be applied to non-LGBT people. Therefore, we want to test the validity of the LGBT Climate Inventory working with a population made up of a complete company staff, including heterosexual population. We want to explore if they observe the climate towards LGBT people similarly, and what are the subgroups in terms of evaluation of the climate towards LGBT people. In this article, we show that LGBT+ and non LGBT+ people can perceive LGBT+ inclusion and argue theoretically and methodologically why this is necessary and what needs to be taken into account. The last decades have not only been marked by advances in the rights of lesbians, gays, trans people, bisexuals and other sexual dissents (hereafter, we shall refer to them all as LGBT+), but also by their social acceptance. Sexual and gender diversity are protected globally in the framework of human rights, particularly by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (Gerber and Gory, 2014; Helfer and Voeten, 2014; MacArthur, 2015; Mulé et al., 2016) and, more recently, by the Yogyakarta Principles (O’Flaherty and Fisher, 2008). At European level, anti-discrimination laws and legislation for the recognition of LGBT+ people have had a special bearing in the workplace, becoming even one of the pillars of the European Union (Maliszewska-Nienartowicz, 2013; Mos, 2013).

In comparative surveys, Spain always stands out among the countries with the highest rates of acceptance of LGBT+ people (Takács et al., 2016) and, in 2005, it was one of the countries that legalized adoption by same-sex couples and egalitarian marriage. Our study took place in Catalonia, a Spanish autonomous community pioneering the implementation of LGBT+ policies in many respects and which, under the pressure of civil society, passed act 11/2014 in order to guarantee the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersexual people and eradicate homophobia, biphobia and transphobia.

Although the Catalan law demands empirical studies and confers special significance to the work environment as a place of implementation LGBT+ policies, there are still few data regarding the reception of sexual and gender diversity in the workplace. One of the problems of the concerned legislation, and of the law in general, is that it is only possible to punish clear and univocal discriminations (Di Marco et al., 2021). Examples of these are same-sex couples that do not enjoy the same advantages as heterosexual ones, or an explicit policy of refusing to hire LGBT+ people. Nevertheless, the problems that LGBT+ people say that they encounter at work, and in ordinary life, often have to do with situations to which anti-discrimination laws are not applicable (Di Marco et al., 2021; Galupo and Resnick, 2016), which only reinforces some forms of prejudice and LGBT-phobic discrimination in the workplace (Moya and Moya-Garófano, 2020). Both the measures and the changes that the affected people demand go beyond the law and what can be changed by legal means (Di Marco et al., 2021; Huffman et al., 2008; Lloren and Parini, 2017; Riley, 2008). These concern something more complex, social and structural, such as workplace atmosphere, culture or climate, as well as micro-acts of aggression at work (Galupo and Resnick, 2016). It is then important to have indicators of friendly climate for sexual and gender diversity, first of all, in order to combat inequality and discrimination (Di Marco et al., 2021; Cech and Rothwell, 2020). In addition, they are also important for the operation itself of organizations, i.e., in order for them to retain their employees as well as to provide them with satisfactory working conditions and, in this way, ensure their productivity (Cech and Rothwell, 2020; Hossain et al., 2020; Rengers et al., 2021). Lastly, there is also an increasing demand, and a will, that organizations are assessed with respect to their corporate social responsibility regarding LGBT+-friendliness (Parizek and Evangelinos, 2021); this involves the development and testing of indicators which are capable of improving friendliness towards sexual and gender diversity. In order to measure whether a particular climate is LGBT+-friendly, Becky Liddle et al. (2004) proposed their LGBT Climate Inventory (LGBTCI).

The LGBTCI was created in a multi-method process (Lewis-Beck et al., 2004) by combining both qualitative and quantitative methodologies (Liddle et al., 2004). In a first stage, LTGB+ people were asked to list situations displaying a friendly climate for sexual and gender diversity, on one hand, and those showing an adverse climate, on the other hand. Based on this list, ten situations expressing a friendly climate for sexual and gender diversity, and five ones which were adverse to it, were formulated (see Table 1).

Table 1. LGBTCI scale

Nº |

Mean |

1 |

[LGBTI+ employees are treated with respect.] |

2 |

[LGBTI+ employees feel accepted by coworkers.] |

3 |

[Non-LGBTI+ employees are comfortable engaging in gay-friendly humour with LGBTI+ employees (for example, kidding them about a date).] |

4 |

[Coworkers are as likely to ask nice, interested questions about a same-sex relationship as they are about a heterosexual relationship.] |

5 |

[LGBTI+ employees feel free to display pictures of a same-sex partner.] |

6 |

[My immediate work group is supportive of LGBTI+ coworkers.] |

7 |

[The company or institution as a whole provides a supportive environment for LGBTI+ people.] |

8 |

[LGBTI+ employees are comfortable talking about their personal lives with coworkers.] |

9 |

[LGBTI+ people consider it a comfortable place to work.] |

10 |

[The atmosphere for LGBTI+ employees is improving.] |

11 |

[LGBTI+ employees are met with thinly veiled hostility (for example, scornful looks or icy tone of voice.] |

12 |

[The atmosphere for LGBTI+ employees is oppressive.] |

13 |

[The men in the staff are expected to not act “too gay”.] |

14 |

[LGBTI+ employees fear job loss because of sexual orientation or gender identity.] |

15 |

[There is pressure for LGBTI+ employees to stay closeted (to conceal their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression).] |

16 |

[The women in the staff are expected to not act “too masculine”.] |

Source: Liddle et al. (2004)

Then, this measuring tool was distributed among LGBT+ people, which enabled its validation by factor analysis. With this, Liddle et al. (2004) contributed to the establishment of one of the most widely used scales for measuring LGBT+-friendliness at work (Webster et al., 2018). Recently, this same tool has been translated into Spanish and its translation has also been validated with the LGBT+ community in the Spanish state (Rivero-Díaz et al., 2020).

It is for this reason that we chose to incorporate the LGBTCI into a survey to determine the reception given to sexual and gender diversity in a public job-placement company devoted to local economic development in Catalonia. When discussing the items included in the LGBTCI with the expert and managing staff at the company, several doubts, questions and suggestions for improvement arose. Firstly, it seemed to them that the tool was too focused on gay and lesbian people. In general, everything was unified under the label LGBT+ but, when specific situations were considered, these had to do with homosexual couples and gay men (in this way, we read about “gay-friendly” environments or about acting in a “gay” way). On the contrary, there were no specific situations relative to bisexual or trans people. This same criticism has been expressed in academic circles concerning LGBTCI in particular (Brewster et al., 2013; Köllen, 2013), and the measuring of friendly work environments for sexual and gender diversity in general (Corrington et al., 2019; Fletcher and Everly, 2021). Despite this, we did not make any profound changes to the LGBTCI; instead, we chose to include these aspects in other sections in our questionnaire.

A second problem with the LGBT Climate Inventory was that the job which was committed to us included an explicit reference to a universalist and non-identitary understanding of sexual and gender diversity. This type of approach, which is close to Judith Butler’s (1990)—it is not so much about what you are but about what you do—and to that of Gerard Coll Planas and Miquel Missé (2014), forced us to enhance those items related to gender expression, as well as to include people who do not self-identify as LGBT+ inasmuch as they may decide not to present themselves as such in the workplace (Alcover, 2018). In line with all the mentioned authors and the managers and experts at the company where our fieldwork took place, we also believe that a friendly climate for sexual and gender diversity can be perceived by everybody, and not only by LGBT+ people; this is also so because sexual and gender diversity goes beyond the identity categories of LGBT+. This does not mean to disregard or leave aside LTGB+ identities, but we seek to go beyond them. In order to confer greater importance to lesbophobia, on one hand, and gender expression, on the other hand, we added a sixteenth item to the original list: [The women in the staff are expected to not act “too masculine”.].

Finally, we found that some items were hard to understand (especially, “gay-friendly humour”) and some others were outdated. Taking into account the fact that the scale was validated both in its English version (Liddle et al., 2004) and, more recently, in its Spanish translation (Rivero Díaz et al., 2020), we kept all the items in the questionnaire regardless of whether they seemed to us difficult to understand or out-of-date. Moreover, we considered that, as the items came from a listing done in the 2000s by LGBT+ people, their content may have become more readily understandable with the increase in rights and tolerance towards the LGBT+ community. After carrying out the survey, we would be able to check whether all the items had worked properly or it was necessary to exclude those who did not fully work.

This said, we can now delineate our objectives. The first one was to check the validity of the scale, with an added item, with a population made up of a complete company staff, including heterosexual population, instead of only people self-identified as LGBT+, as it had previously been done. Secondly, we aimed to identify the underlying structure regarding the appraisal of the climate for sexual and gender diversity in the analysed company. Thirdly, we wanted to check whether such structure displayed differentiated patterns by sub-groups depending on sexual orientation, position in the company’s hierarchy, and sex-gender variables. Finally, as the questionnaire was used in Catalan, our research would also be used to validate it as measuring tool in this language.

Methodology

Methodologically, this paper relies on a quantitative methodology. While feminist methodologies are traditionally linked to qualitative methods, we do support the idea that, in Kevin Cokley’s and Germine Awad’s words, the “master’s tools” can help promote social justice (2013). However, in our case, we are not satisfied with a simple “add women” strategy, often criticized as feminist empiricism (Biglia and Vergés, 2016). We assume Harding’s contribution regarding the epistemic privilege of affected subjects and the feminine standpoint (1987). Thus, we depart from a measuring tool created from the standpoint of LGBT+ people, like the LGBTCI. Nevertheless, we also think that the perception of the climate for sexual and gender diversity in a company does not only concern those who identify themselves as LGBT+—also because we hold that any identitarian approach of this sort leaves out important aspects of sexual and gender diversity. This is why, while we do not exclude from our study the partisan analysis of self-identified LGBT+ people, we carry out a sort of “add straight people” strategy, i.e., we resort to measures which have been formulated in the frame of the epistemic privilege of marginalized people. In this sense, we react to that criticism of quantitative methodologies that attributes them the creation of androcentric theoretical constructs. However, for the appraisal of such marginalized discourse, we do include all the actors, because we believe that all voices and experiences matter. In a certain way, we make Harding’s journey (1987) and we stress the importance of Haraway’s (1988) situated knowledge, where the multiplication of standpoints matters in order to build a veracious image. Thus, we rescue the proposals of methodological pluralism made by feminist epistemology while incorporating the LGBT+ point of view and universalizing a vision on the climate for LGBT+ people that takes all perspectives into account.

About the questionnaire

The data which are analysed come from a survey carried out in one of the main public job-placement companies devoted to the promotion of local economic development in Catalonia. The sixteen items concerning the company’s climate for sexual and gender diversity are placed in the middle of a questionnaire which revolves around issues related to sexual and gender diversity. It includes questions about the respondent’s position regarding LGBT+-phobia, their perception of climate and their assessment of policies addressed to promote a friendly climate for sexual and gender diversity. In order to preserve the respondent’s anonymity, sociodemographic information was collected only about the person’s rank in the company (wages and information on whether they had workers under their command), their sexual identity and their gender identity.

To grasp the existing climate for sexual and gender diversity, the LGBT Climate Inventory was used. The LGBT Climate Inventory is made up of 15 items selected on the base of a qualitative study of the experiences of LGBT+ people at work. They describe ten situations which reflect a friendly climate for diversity and five additional situations describing an adverse climate for sexual and gender diversity. At the company’s request, and in relation to the commissioned task, we added a new item depicting a positive situation as well and concerning women’s gender expression. This was also a response to the need found by recent research of formulating specific items to acknowledge lesbian people and capture the importance of the role played by gender expression (De Simone and Priola, 2022; Hamilton et al., 2019). The response categories express the degree to which these situations describe the company’s climate: “not at all,” “a little,” “pretty well,” and “extremely well.”

About the data

The surveyed population was the whole staff at the company; we did not work with a sample, but with the complete roll. It must be pointed out that the analysed personnel was highly feminized (77.25 percent of women) and most employees were paid between €30 000 and €40 000 a year (60.4 percent). Data were collected by means of an online survey using the LimeSurvey software for four weeks in June-July, 2021.

In general, response rate was low: 31.76 percent of the employees answered the questionnaire. It was relatively high for the employees in the upper-middle range of income, and lower for those in the lowest and lower-middle income range. Men displayed a lower response rate than women.

As for the composition of the respondents’ roll, the prevailing groups are people whose income ranges between €30 000 and €40 000 a year (60.4 percent), with no workers under their command (69.9 percent) and women (81.8 percent). As far as sexual and gender diversity are concerned, 4 percent self-identified as non-binary people, and 25 percent as non-heterosexuals, more than half of whom identified themselves as bisexual, 3 percent as other non-normative orientations, 3 percent as lesbians and 1 percent as gay.

In this sense, it is important to highlight a fundamental limitation: self-selection (Díaz de Rada, 2011). With a response rate of slightly over 30 percent, it is probable that the survey was answered more by people related to or interested in issues of sexual and gender diversity. Thanks to other items in the questionnaire, we know that people are much more inclusive with LGBT+ people than it is common; this suggests to us that the survey was answered by people who are sympathetic towards sexual and gender diversity, whether because someone in their family or among their friends is LBTG+, because their values or their ideology are aligned with tolerance towards LGBT+ people, or because they themselves self-identify as LGBT+.

About the techniques

Technically, we carried out a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) in order to assess the functioning of LGBTCI. This technique is suitable to assess indicators’ systems made up of qualitative variables (López-Roldán and Fachelli, 2015; Domínguez Amorós and Solsona Simó, 2003). The aim of correspondence analysis is to find underlying structures in databases (Greencare, 2008). Here, we search for an underlying structure in the 16 items measuring different aspects related to the work climate towards sexual and gender diversity. This same analysis can be used to assess how the company staff perceives sexual and gender diversity and whether there exist substantial differences between groups (López Roldán, 1996).

Returning to the LGBTCI, as we see in table 1, “don’t know” answers and those depicting a friendly climate for sexual and gender diversity prevail. Some of the answers describing a less friendly climate for sexual and gender diversity have very low frequencies. As one of the requirements of simple correspondence analysis is that response frequency is near 5 percent, the affected variables are re-codified by unifying the cells marked in bold (Table 2).

Table 2. Answer frequencies

Item |

Not at all |

A little |

Pretty well |

Extremely Well |

Don’t know |

N |

1 |

0.00 |

4.65 |

14.73 |

57.36 |

23.26 |

129 |

2 |

1.55 |

1.55 |

13.18 |

44.96 |

38.76 |

129 |

3 |

4.62 |

5.38 |

16.92 |

18.46 |

54.62 |

130 |

4 |

6.15 |

9.23 |

23.08 |

25.38 |

36.15 |

130 |

5 |

3.10 |

6.98 |

17.05 |

33.33 |

39.53 |

129 |

6 |

0.78 |

3.10 |

13.18 |

58.91 |

24.03 |

129 |

7 |

0.78 |

10.85 |

25.58 |

44.19 |

18.60 |

129 |

8 |

3.08 |

10.77 |

20.00 |

22.31 |

43.85 |

130 |

9 |

0.00 |

6.15 |

16.92 |

32.31 |

44.62 |

130 |

10 |

1.55 |

6.98 |

21.71 |

31.78 |

37.98 |

129 |

11 |

36.72 |

14.06 |

3.13 |

0.78 |

45.31 |

128 |

12 |

46.09 |

10.16 |

2.34 |

3.91 |

37.50 |

128 |

13 |

54.76 |

10.32 |

7.94 |

1.59 |

25.40 |

126 |

14 |

51.16 |

10.85 |

2.33 |

0.78 |

34.88 |

129 |

15 |

65.89 |

7.75 |

4.65 |

0.00 |

21.71 |

129 |

16 |

54.26 |

16.28 |

5.43 |

4.65 |

19.38 |

129 |

Thus, we start out with a first dimensionalization, with as many variables as response categories minus active variables (70-16 = 54, see Table 3) (López-Roldan and Fachelli, 2015). We calculate Cronbach’s alpha, which tells us the factors’ internal consistency and gives us the first results for 54 possible factors. Then we perform the Jean Paul Benzécri correction (1979) of eigenvalues, which are too pessimistic in the MCA. Based on bidimensional distribution graphs generated from the extracted factors, we check whether different groups of employees have different views about the work climate. The obtained graphic results are then corroborated by an analysis of means.

Table 3. Calculation of possible dimensions

Number of categories |

(5 categories * 6 variables) + (4 categories * re-codified 10 variables) |

70 |

Number of variables |

16 variables of analysis 5 complementary variables |

16 |

Number of possible dimensions |

|

54 |

Univariant results

With respect to the response rate of the different items, we do not observe any relevant differences between the 16 items. For all of them, it ranges between 126 and 130 responses. However, there are important differences in relation to the “don’t know” answer. This is a tricky response category because we do not precisely know what it means; it may mean “I don’t understand the item,” but it may also mean “I understand the item, but I don’t know the answer, i.e., I don’t dare to say how well it describes the company’s situation.”

This said, it must be highlighted that the single item with over half the respondents answering “don’t know” (54.62 percent) was “Non-LGBTI+ employees are comfortable engaging in gay-friendly humour with LGBTI+ employees (for example, kidding them about a date),” which may confirm the suspicions of company managers and experts that this item was not suitable. In the following items, the percentage of “don’t know” answers is between 40 percent and 50 percent:

-LGBTI+ employees are comfortable talking about their personal lives with coworkers.

-LGBTI+ people consider it a comfortable place to work.

-LGBTI+ employees are met with thinly veiled hostility (for example, scornful looks or icy tone of voice.

The items with the lowest rates of “don’t know” answers (18%-30%) are:

-The company or institution as a whole provides a supportive environment for LGBTI+ people.

-The women in the staff are expected to not act “too masculine”.

-There is pressure for LGBTI+ employees to stay closeted (to conceal their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression).

-LGBTI+ employees are treated with respect.

-My immediate work group is supportive of LGBTI+ coworkers.

-The men in the staff are expected to not act “too gay”.

In the rest of items, the percentage of people who answered “don’t know” ranges between 30 percent and 40 percent.

In this sense, it should be stressed that the rate of “don’t know” answers is very high, and we do not know whether these correspond to items which are difficult to understand or whether the respondents could not decide if the related situations describe or not the company’s climate. What we perceive is that the items with lowest “don’t know” rates are relative to situations where the subject is the company or its whole staff, while those items with the highest rates correspond to items where the subject is LGBT+ people.

As for the “not at all”, “a little”, “pretty well” and “extremely well” responses, the vast majority of answers always goes for those categories that approve of the company’s work climate as open to sexual and gender diversity. There are only 6 (out of 16) items where more than 10 percent of respondents stated that there exists a rather adverse climate for sexual and gender diversity. These items are:

-Coworkers are as likely to ask nice, interested questions about a same-sex relationship as they are about a heterosexual relationship.

-LGBTI+ employees feel free to display pictures of a same-sex partner.

-The company or institution as a whole provides a supportive environment for LGBTI+ people.

-Non-LGBTI+ employees are comfortable engaging in gay-friendly humour with LGBTI+ employees (for example, kidding them about a date).

-LGBTI+ employees are comfortable talking about their personal lives with coworkers.

-The women in the staff are expected to not act “too masculine”.

Results of the Multiple Correspondence Analysis for the 16-item LGBT Climate Inventory

As the Cronbach’s alpha indicates (see Table 4), both dimensions display excellent internal consistency, which means that they are coherent. This fact also validates our measuring instrument, as this produces consistent data: eventually, all 16 items measure the same concept. However, when we take into consideration the discriminant measures, it must be said that most of the analysed variables are only partially captured by the extracted factors (Appendix I, Table 1). This affects particularly the second dimension.

Table 4. Internal consistency and axes’ summarized inertia

|

Cronbach’s alpha |

% of corrected eigenvalues |

First dimension (Comprehension) |

0.939 |

51.31 |

Second dimension (Appraisal of LGBT+ climate) |

0.917 |

35.93 |

The first dimension explains 51.31 percent of variance in the perceptions of the climate for sexual and gender diversity. Taken together, they explain 87.24 percent of the total variance. This means that, with only two factors, we can summarize almost 90 percent of the information given by the 16 original variables regarding the climate for sexual and gender diversity at the analysed public job company.

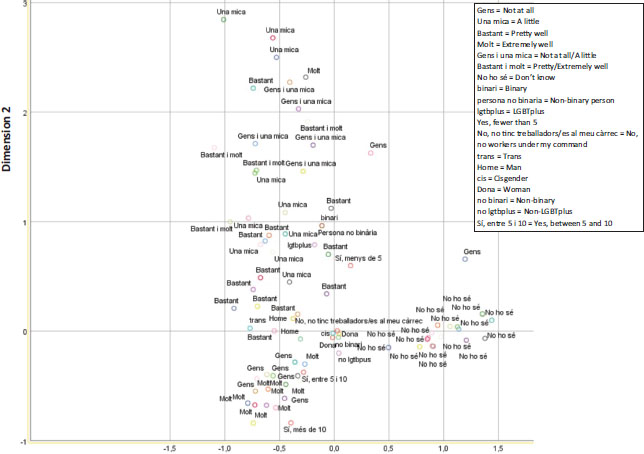

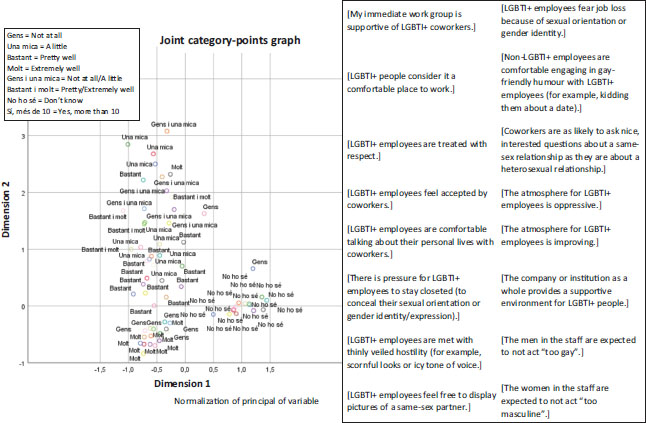

On analysing the content of dimensions, we see that the first dimension (the horizontal axis)—the main one insofar as it summarizes 51.31 percent of inertia—basically opposes “don’t know” responses to all the rest (see Figure 1 and Figure 2). Thus, we can name this first axis as that of the comprehension of problems linked to a friendly climate toward sexual and gender diversity. It distinguishes between those respondents who understand the item and take a stance, and those who do not fully comprehend it or do not know what to answer.

Figure 1. Response categories points

Figure 2. Response categories points, with legend

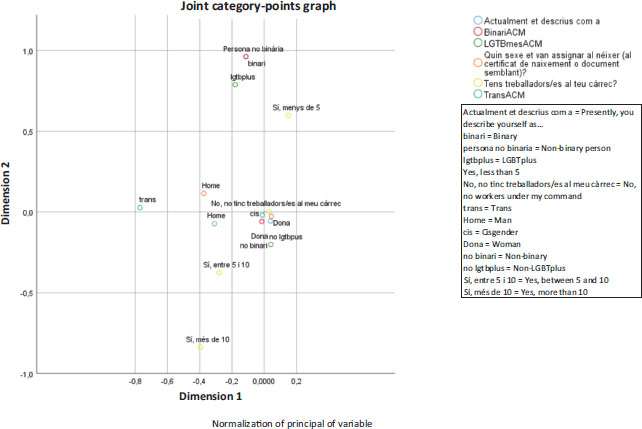

If we take into consideration the sociodemographic variables that are not part of the multiple correspondence analysis but were subsequently added in the way of illustration, we observe that the points for “woman” (as assigned at birth and present identity), “binary person”, “cisgender” and “no workers under their command” concentrate around the centre of gravity (see Figure 1 and Figure 3). This is partly due to the fact that these are the prevailing categories and, as such, they define the centre of gravity when we consider the total variance in the field.

Figure 3. Response-category points of illustrative sociodemographic variables

When we consider the first axis, we see that trans people, men (as assigned at birth and present identity), people with more than 5 employees under their command, non-binary people and LGBT+ usually know what to answer, while those with fewer than 5 employees under their command tend to answer “don’t know” (see Figure 1 and Figure 3). As for the second dimension—actual appraisal of company’s climate—, we find that non-binary people, those who self-identify as LGBT+, and those with fewer than 5 employees under their command appear on the side of the graph meaning the lowest assessment of the company’s climate, while people with more than 5 employees under their command, non-binary nor LGBT+ appear on the opposite end (see Figure 1 and Figure 3).

Basically, the second dimension opposes those responses that describe a friendly climate for sexual and gender diversity to those which depict a more adverse climate. It is important to underline that this dimension, which should be the principal one, only summarizes 35.9 percent of variance and, thus, it clearly stands in a second place when it comes to structuring the perceptions of climate toward sexual and gender diversity.

Turning back to discriminant measures (see Figure 4), we should stress that the two factors are not clearly distinguished from each other by the variables that contribute to them (or that are correlated by them) but by the response categories: the response category “don’t know” contributes to the first factor, while the second factor comprises the contributions of the different response categories actually assessing the climate. We see a slight bent towards the former (not knowing how to answer) in the following four items:

-LGBTI+ employees are met with thinly veiled hostility (for example, scornful looks or icy tone of voice).

-The atmosphere for LGBTI+ employees is oppressive.

-LGBTI+ employees fear job loss because of sexual orientation or gender identity.

-There is pressure for LGBTI+ employees to stay closeted (to conceal their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression).

Figure 4. Discriminant measures

On the contrary, the two following items display a slight bent toward the second factor:

-The company or institution as a whole provides a supportive environment for LGBTI+ people.

-The men in the staff are expected to not act “too gay”.

The included sociodemographic variables (see Figure 5), such as self-identifying as LGBT+, having employees under one’s command and self-identifying as non-binary, also contribute more to the second factor.

Figure 5. Discriminant measures with illustrative variables

Profiles

So far, we have focused on the location of response categories in the coordinates. However, we can also place individuals on the same axis. When we consider the several sociodemographic variables, at first sight, we do not see any differentiated patterns according to response categories. However, if we perform a Student’s T-test, we observe that, in the second factor, LGBT+ people distinguish themselves from non-LGBT+, and non-binary people, from binary people (see Table 5). The test corroborates that LGBT+ people do not display any difference in terms of knowing what to answer, but those who do know what to answer tend to assess the company’s climate for sexual and gender diversity worse than non-LGBT+ people. We see the same in the case of non-binary people.

Table 5. Means comparison for Factors and LGBT+, binary and sex at birth

LGBT+ |

F |

Sig. |

T |

Sig. |

Means difference |

First Factor (Comprehension) |

2.695 |

0.104 |

0.149 |

0.882 |

0.0369 |

Second Factor (Appraisal of LGBT+ Climate) |

18.814 |

0.000 |

-4.215* |

0.000 |

-1.0889 |

Binary |

F |

Sig. |

T |

Sig. |

Means difference |

First Factor (Comprehension) |

1.627 |

0.205 |

-0.015 |

0.988 |

-0.0089 |

Second Factor (Appraisal of LGBT+ Climate) |

1.311 |

0.255 |

2.091* |

0.039 |

1.0705 |

Sex at birth |

F |

Sig. |

T |

Sig. |

Means difference |

First Factor (Comprehension) |

2.377 |

0.126 |

-1.684 |

0.095 |

-0.4814 |

Second Factor (Appraisal of LGBT+ Climate) |

0.090 |

0.756 |

0.883 |

0.379 |

0.2361 |

Discussion

After seeing its results, our research makes an important contribution on the applicability of the LGBTCI measuring instrument. While the existing research had only applied it to the LGBT community (Liddle et al., 2004; Rivero Díaz et al., 2020), in our research, we applied it to the whole staff in one company. With this, we pioneered the application of LGBTCI to both LGBT+ and non-LGBT+ people, showing that it works equally well with both groups. Besides this, we have a more clearly defined LGBT+ people universe and we mitigate the problem of self-selection seen in many previous applications of the LGBTCI, where surveys were carried out mainly online with people who identified themselves as LGBT+, reproducing a selection bias which is typical when one works with LGBT+ people (Schrager et al., 2019).

Taking into account the low participation in our survey, also compared to other surveys carried out by the employer, we conclude that the employee should foster participation explicitly. It is important to make employees understand that the inclusion of sexual and gender diversity affects everybody in the organization and that participating in a monitoring survey is required.

With regard to our to sample selection, our study reveals that there is a vast majority of LGBT+ people who identify themselves as bisexuals. This result differs from other studies due to the fact that bisexual people do not self-select in surveys addressed to LGBT+ people since the issue of sexual identity does not carry much weight in their identity self-construction (Doan and Mize, 2020). On the contrary, as we did not address exclusively LGBT+ people but the whole staff in a particular, well-defined company, bisexual people did answer the questionnaire, turning out to be about three quarters of all LGBT+ respondents. A survey which is addressed to the whole company staff is more likely to attract bisexual employees who would not have possibly answered a questionnaire addressed to LGBT+ employees. For the future, this implies to apply the LGBTCI not through a self-selection appealing mainly to LGBT identified persons, but to a whole enterprise. In doing so LGBT people for whom sexual identity is not that relevant for their identity construction, as for many bisexuals, are more easily recruited. In this sense we strongly recommend implementing the LGBTCI in well-defined context such as determined organizations, public administrations or firms.

Also, in terms of sample, it is important to construct bigger samples in order to carry out more intersectional analysis. With our sample size, it is difficult to check very specific intersectionalities (e.g. racialization and sexual orientation or disability) as we do not have enough respondents. Here it is important to rise the responds quote on the hand, and on the other hand, it might be beneficial to implement the same questionnaire at different organizations. Taking into account that big cities such as Barcelona always imply a certain bias in terms of inclusion of sexual and gender diversity, it is also interesting to perform these analysis in enterprises situated in less metropolitan contexts. Taking into account the composition of our sample as well as the comments of the equality officer, for the future there is a need to add new items to capture specific problems of bisexuality (Brewster et al., 2013; Corrington et al., 2019; Fletcher and Everly, 2021; Köllen, 2013), trans-people and other non-normative gender-expressions.

As for the underlying structure displayed by the responses in relation to the items, two factors should be highlighted: on one hand, employees differ in their ability to answer the different items and, on the other hand, with respect to their perceptions of the degree of observed inclusion and exclusion in the company. In this sense, the achieved results differ from the previous results obtained by Liddle et al. (2004) and María Rivero Díaz et al. (2020) in the fact that they only find dimensions related to climate perception, and not to the respondents’ knowledge of the items and their ability to respond to them. In addition, and in contrast with the aforementioned authors (Liddle et al., 2004; Rivero-Díaz et al., 2020), the dimensions obtained by us take into account both LGBT+ and non-LGBT+ people. It is important to underline that LGBT+ and non-LGBT+ populations only display very slight different patterns of item comprehension, except for the item about gay-friendly humour and, globally, with reference to the first factor. What we see though is that both, LGBT+ and non-LGBT+ respondents often respond “I don’t know” which may indicate that there is no profound comprehension or interest in the situation of LGBT+ people. Organizational policies need to address this and create awareness of diversity management.

On the other hand, there are differences in the way LGBT+ people perceive the company’s climate: LGBT+ people agree more often that there are situations of exclusion, and they agree less often that there are situations of inclusion. In this sense, our results indicate that not only LGBT+ people are able to discern the climate towards sexual and gender diversity, in line with the commissioned task of adopting a not-so-identitary perspective in our research on how to include sexual and gender diversity (Coll-Planas and Missé, 2014) without totally disregarding the perceptions that the main affected communities have (Harding, 1987). If we want to assess the climate concerning sexual diversity, non binary and LGBT+ people should always be taken into account, as they have a privileged and slightly different perception. However, non-LGBT+ people do not differ that strongly and should be included, too.

To put it in a nutshell, from these results, two main implications follow for future research: surveys on the perception of climate for sexual and gender diversity should comprise the whole company staff and not only those who identify themselves as LGBT+, although the perceptions of LGBT+ people should not be disregarded. On the other hand, the LGBTCI should also include items about the experiences of bisexual and trans people.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to Màrius Domínguez Amorós and Núria Vergés Bosch for their collaboration on this project. We also wish to thank the organization we partnered with for this assessment, including their staff and those responsible for equality and non-discrimination efforts.

Funding

Leon Freude has coordinated the project with the collaborating organisation. For the scientific analysis of the data he has benefitted from a PhD grant from the Ministry of Science, Innovation and University (FPU18/02501) and a post-doctoral grant from the same funder (JDC2023-050628-I).

References

Alcover, Carlos María. (2018). Who are ‘I’? Who are ‘we’? A state-of-the-art review of multiple identities at work. Psychologist Papers, 39, 200–207. https://doi.org/10.23923/pap.psicol2018.2858

Benzécri, Jean Paul. (1979). Sur le calcul des taux d’inertie dans l’analyse d’un questionnaire. Les Cahiers de l’Analyse des Données, 4, 377–378.

Biglia, Barbara & Vergés Bosch, Núria. (2016). Cuestionando la perspectiva de género en la investigación. REIRE. Revista d’Innovació i Recerca en Educació, 9(2), 12–29. https://doi.org/10.1344/reire2016.9.2922

Brewster, Melanie E.; Moradi, Bonnie; DeBlaere, Cirleen & Velez, Brandon L. (2013). Navigating the borderlands: the roles of minority stressors, bicultural self-efficacy, and cognitive flexibility in the mental health of bisexual individuals. Journal of counseling psychology, 60(4), 543. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033224

Butler, Judith. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

Cech, Erin A. & Rothwell, William R. (2020). LGBT workplace inequality in the federal workforce: Intersectional processes, organizational contexts, and turnover considerations. ILR Review, 73(1), 25–60. https://doi.org/10.1177/0019793919843508

Cokley, Kevin & Awad, Germine H. (2013). In defense of quantitative methods: Using the “master’s tools” to promote social justice. Journal for Social Action in Counseling & Psychology, 5(2), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.33043/JSACP.5.2.26-41

Coll-Planas, Gerard & Missé, Miquel. (2014). “Me gustaría ser militar”: Reproducción de la masculinidad hegemónica en la patologización de la transexualidad. Prisma Social, 13, 407–432.

Corrington, Abby; Nittrouer, Christine L.; Trump-Steele, Rachel C. & Hebl, Mikki. (2019). Letting him B: A study on the intersection of gender and sexual orientation in the workplace. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 113, 129–142.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2018.10.005

De Simone, Silvia & Priola, Vincenza. (2022). “Who’s that girl?” The entrepreneur as a super (wo)man. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 39(1), 97–111. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1643

Díaz de Rada, Vidal. (2011). Encuestas con encuestador y autoadministradas por internet: ¿Proporcionan resultados comparables? Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas (REIS), 136(1), 49–90. https://doi.org/10.5477/cis/reis.136.49

Di Marco, Donatella; Hoel, Helge & Lewis, Duncan. (2021). Discrimination and exclusion on grounds of sexual and gender identity: Are LGBT people’s voices heard at the workplace? The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 24. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2021.16

Doan, Long & Mize, Trenton D. (2020). Sexual identity disclosure among lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Sociological Science, 7, 504–527. https://doi.org/10.1017/10.15195/v7.a21

Domínguez i Amorós, Màrius & Simó Solsona, Montserrat. (2003). Tècniques d’investigació social quantitatives. Edicions Universitat de Barcelona.

Fletcher, Luke & Everly, Benjamin A. (2021). Perceived lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) supportive practices and the life satisfaction of LGBT employees: The roles of disclosure, authenticity at work, and identity centrality. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 94(3), 485-508. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12336

Galupo, M. Paz & Resnick, Courtney A. (2016). Experiences of LGBT microaggressions in the workplace: Implications for policy. En Thomas Köllen (Ed.), Sexual orientation and transgender issues in organizations (pp. 271–287). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-29623-4_16

Gerber, Paula & Gory, Joel. (2014). The UN Human Rights Committee and LGBT rights: What is it doing? What could it be doing? Human Rights Law Review, 14(3), 403–439. https://doi.org/10.1093/hrlr/ngu019

Greencare, Michael. (2008). La práctica del análisis de correspondencias. Fundación BBVA.

Hamilton, Kelly M.; Park, Lauren S.; Carsey, Timothy A. & Martinez, Larry R. (2019). “Lez be honest”: Gender expression impacts workplace disclosure decisions. Journal of Lesbian Studies, 23(2), 144–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2019.1520540

Haraway, Donna. (1988). Situated knowledges: The science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Feminist Studies, 14(3), 575–599.

Harding, Sandra. (1987). Introduction: Is there a feminist method? En Sandra Harding (Ed.), Feminism and methodology (pp. 1–14). Indiana University Press.

Helfer, Laurence R. & Voeten, Erik. (2014). International courts as agents of legal change: Evidence from LGBT rights in Europe. International Organization, 68(1), 77–110. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020818313000398

Hossain, Mohammed; Atif, Muhammad; Ahmed, Ammad & Mia, Lokman. (2020). Do LGBT workplace diversity policies create value for firms? Journal of Business Ethics, 167(4), 775–791. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04158-z

Huffman, Ann H.; Watrous‐Rodriguez, Kristen M. & King, Eeden B. (2008). Supporting a diverse workforce: What type of support is most meaningful for lesbian and gay employees? Human Resource Management, 47(2), 237-253. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20210

Köllen, Thomas. (2013). Bisexuality and diversity management: Addressing the B in LGBT as a relevant ‘sexual orientation’ in the workplace. Journal of Bisexuality, 13(1), 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2013.755728

Lewis-Beck, Michael S.; Bryman, Alan & Liao, Tim F. (2004). Multimethod research. In The SAGE encyclopedia of social science research methods (Vol. 1, pp. 678–681). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412950589.n592

Liddle, Becky J.; Luzzo, Darrell A.; Hauenstein, Anita L. & Schuck, Kelly. (2004). Construction and validation of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered climate inventory. Journal of Career Assessment, 12(1), 33–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072703257722

Lloren, Anouk & Parini, Llorena. (2017). How LGBT-supportive workplace policies shape the experience of lesbian, gay men, and bisexual employees. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 14(3), 289–299. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-016-0253-x

López-Roldán, Pedro. (1996). La construcción de tipologías: Metodología de análisis. Papers: Revista de Sociologia, 9–29. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/papers.1812

López-Roldán, Pedro & Fachelli, Sandra. (2015). Metodologías de investigación social cuantitativa (MISC). Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.

MacArthur, Gemma. (2015). Securing sexual orientation and gender identity rights within the United Nations framework and system: Past, present and future. The Equal Rights Review, 15, 25–54.

Maliszewska-Nienartowicz, Justyna. (2013). Sexual orientation discrimination in the case-law of the Court of Justice of the EU: A revolution or steady progress? Contemporary Legal and Economic Issues, 4(9), 9-28

Mos, Martijn. (2013). Conflicted normative power Europe: The European Union and sexual minority rights. Journal of contemporary European research, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.30950/jcer.v9i1.410

Moya, Miguel Carlos & Moya-Garófano, Alba. (2020). Discrimination, work stress, and psychological well-being in LGBTI workers in Spain. Psychosocial Intervention, 29(2), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.5093/pi2020a5

Mulé, Nick J.; McKenzie, Cameron & Khan, Maryam. (2016). Recognition and legitimisation of sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) at the UN: A critical systemic analysis. British Journal of Social Work, 46(8), 2245–2262. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcw139

O’Flaherty, Michael & Fisher, John. (2008). Sexual orientation, gender identity and international human rights law: contextualising the Yogyakarta Principles. Human Rights Law Review, 8(2), 207-248.

Parizek, Katharina & Evangelinos, Konstantinos I. (2021). Corporate social responsibility strategies and accountability in the UK and Germany: Disclosure of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender issues in sustainability reports. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(3), 1055–1065. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2105

Rengers, Julian M.; Heyse, Liesbet; Wittek, Rafael P. & Otten, Sabine. (2021). Interpersonal antecedents to selective disclosure of lesbian and gay identities at work. Social Inclusion, 9(4), 388–398. https://doi.org/10.17645/si.v9i4.4591

Riley, Donna M. (2008). LGBT-friendly workplaces in engineering. Leadership and Management in Engineering, 8(1), 19–23. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1532-6748(2008)8:1(19)

Rivero-Díaz, Maria L.; Agulló-Tomás, Esteban & Llosa, Jose Antonio. (2020). Adaptation and validation of the LGBTCI to the Spanish LGBT working population. Journal of Career Assessment, 1069072720982339. https://doi.org/10.1177/1069072720982339

Schrager, Sheree M.; Steiner, Riley J.; Bouris, Alida M.; Macapagal, Kathryn & Brown, C. Hendricks. (2019). Methodological considerations for advancing research on the health and wellbeing of sexual and gender minority youth. LGBT Health, 6(4), 156–165. https://doi.org/10.1089/lgbt.2018.0141

Takács, Judith; Szalma, Ivett & Bartus, Tamás. (2016). Social attitudes toward adoption by same-sex couples in Europe. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(7), 1787–1798. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0691-9

Webster, Jennica R.; Adams, Gary A.; Maranto, Cheryl L.; Sawyer, Katina & Thoroughgood, Christian. (2018). Workplace contextual supports for LGBT employees: A review, meta‐analysis, and agenda for future research. Human Resource Management, 57(1), 193–210. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21873

APPENDIX I

Table 1. Discriminant measures

No. |

Item |

Dimension 1 |

Dimension 2 |

Mean |

1 |

[LGBTI+ employees are treated with respect.] |

0,583 |

0,586 |

0,584 |

2 |

[LGBTI+ employees feel accepted by coworkers.] |

0,557 |

0,518 |

0,538 |

3 |

[Non-LGBTI+ employees are comfortable engaging in gay-friendly humour with LGBTI+ employees (for example, kidding them about a date).] |

0,473 |

0,456 |

0,465 |

4 |

[Coworkers are as likely to ask nice, interested questions about a same-sex relationship as they are about a heterosexual relationship.] |

0,474 |

0,387 |

0,43 |

5 |

[LGBTI+ employees feel free to display pictures of a same-sex partner.] |

0,551 |

0,596 |

0,574 |

6 |

[My immediate work group is supportive of LGBTI+ coworkers.] |

0,424 |

0,255 |

0,339 |

7 |

[The company or institution as a whole provides a supportive environment for LGBTI+ people.] |

0,366 |

0,529 |

0,447 |

8 |

[LGBTI+ employees are comfortable talking about their personal lives with coworkers.] |

0,499 |

0,471 |

0,485 |

9 |

[LGBTI+ people consider it a comfortable place to work.] |

0,59 |

0,631 |

0,611 |

10 |

[The atmosphere for LGBTI+ employees is improving.] |

0,505 |

0,544 |

0,524 |

11 |

[LGBTI+ employees are met with thinly veiled hostility (for example, scornful looks or icy tone of voice.] |

0,646 |

0,263 |

0,455 |

12 |

[The atmosphere for LGBTI+ employees is oppressive.] |

0,662 |

0,251 |

0,457 |

13 |

[The men in the staff are expected to not act “too gay”.] |

0,324 |

0,501 |

0,412 |

14 |

[LGBTI+ employees fear job loss because of sexual orientation or gender identity.] |

0,671 |

0,376 |

0,523 |

15 |

[There is pressure for LGBTI+ employees to stay closeted (to conceal their sexual orientation or gender identity/expression).] |

0,572 |

0,342 |

0,457 |

16 |

[The women in the staff are expected to not act “too masculine”.] |

0,456 |

0,439 |

0,447 |

Illustrative variables |

Sexual identity Sex assigned at birth Workers under their command Trans Binary LGB+ |

0,012 0,021 0,017 0,005 0,001 0,008 |

0,031 0,002 0,086 0 0,031 0,157 |

0,022 0,012 0,051 0,002 0,016 0,082 |

Leon Freude

Postdoctoral researcher at Pompeu Fabra University. PhD in Sociology (Universitat de Barcelona) on Homonationalism. Master in Gender Studies (Interuniversitarian Institute of Women’s and Gender Studies) and Research Techniques for Applied Social Sciences (Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona). His main research interests are to deal with contemporary queer-feminist debates through quantitative methods.

leon.freude@upf.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2284-9817

Jordi Bonet-Martí

Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Barcelona. Holds a PhD in Social Psychology and is a member of the COPOLIS research group on Welfare, Community, and Social Control. His main research interests focus on feminist methodologies and reactions to feminism.

jordi.bonet@ub.edu

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8863-3202

Formato de citación

Freude, Leon & Bonet-Martí, Jordi. (2025). LGBT Climate Inventory in Corporations for Straight People? Quaderns de Psicologia, 27(1), e2107. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/qpsicologia.2107

Historia editorial

Recibido: 04-12-2023

Aceptado: 30-12-2024

Publicado: 01-04-2025